“You’ve been doing this for two weeks, sister,” Woodfin playfully chided her. “I don’t know why you’re doubting yourself.”

Years ago, when Woodfin attended Union Public Schools from kindergarten through eighth grade, she sat in fairly homogenous classrooms. Woodfin recalled her peers as predominantly white, a legacy of families moving to the suburbs as Tulsa schools desegregated during the 1950s. But when she returned to teach at Union in 2012, the white student population had shrunk to a little more than half of total enrollment.

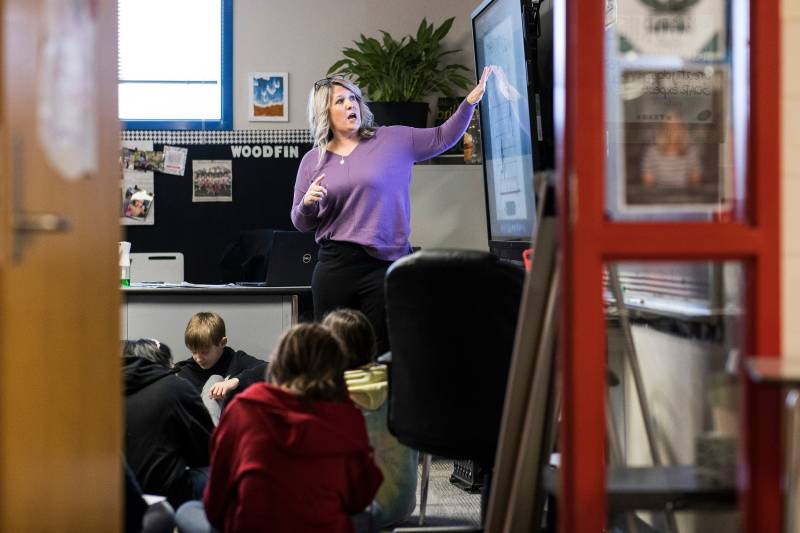

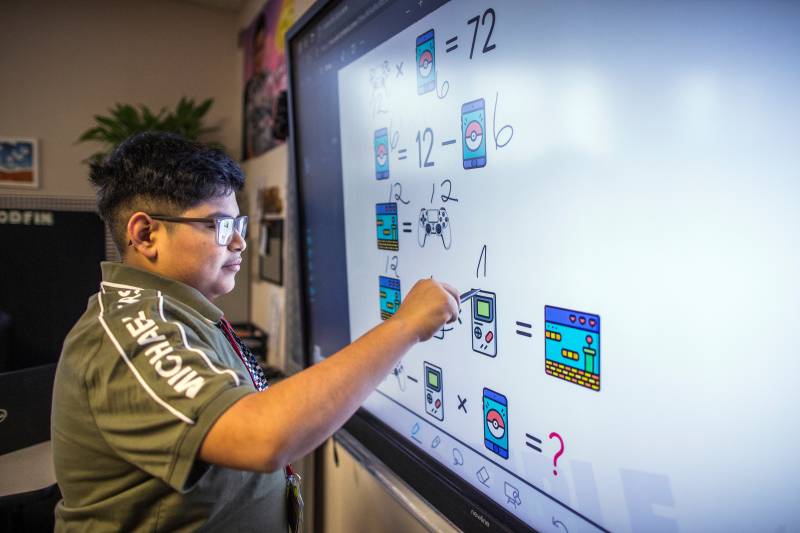

Until recently, however, students in Union’s advanced math classes remained mostly white. The accelerated track in middle and high school drew mostly from elementary schools in affluent neighborhoods, where students tended to perform better on a pre-algebra placement test that they had one chance to take as fifth graders. But on a recent winter day, only two of Woodfin’s students identified as white and more than a third were still learning English.

The transformation of Woodfin’s class rosters represent more than a general shift in who attends Union schools, where today only one in four students is white. It’s also the result of a years-long campaign to identify and promote more students from underrepresented backgrounds into the district’s most challenging math courses.

Elsewhere, concerns about who gets access to advanced math have led districts to end the tracking of students into different math classes by perceived ability or to remove accelerated classes altogether in the name of equity. Union, by contrast, has attempted to find a middle ground. The district, which overlaps part of Tulsa and its southeast suburbs, continues to track students into separate math classes beginning in sixth grade. But it has also added new ways beyond the one-time placement test for students to qualify for higher level math courses, and increased support — including in-school tutoring and longer class periods — for students who’ve shown promise in the subject.

Enrollment data suggest the effort to make higher-level math accessible to more students had started to yield results before the pandemic. But there have been challenges: In the last few years, fewer students overall have enrolled in advanced math classes, although the declines for Black and Hispanic students have been less steep than for other groups. Anti-teacher sentiment, on top of Oklahoma’s low teacher salaries, have made it difficult to hire math educators, administrators here say. At Union High School, an Algebra 2 position remained vacant for more than a year.

But the district remains committed to its changes. Recently, principals and veteran math educators have persuaded some former students to join Union’s teaching ranks. Shannan Bittle, a secondary math specialist for Union, said new academic programs — like aviation and construction — could offer students more ways to apply higher levels of math in lucrative jobs.

“We try really, really hard not to keep people out” of accelerated math, she said. “But we do our best to give them the tools to succeed.”

Taking algebra or higher in middle school places a student on the path to calculus in high school, which opens the door to selective colleges and is considered a gateway course for many high-paying STEM careers. Federal education data shows white students enroll in high school calculus at nearly eight times the rate of their Black peers and about triple the average for Hispanic students.

“There are many Black and Latino students and students from low-income backgrounds who have demonstrated an aptitude and are yearning for more — yet they are systemically denied access to advanced math courses,” wrote the authors of a December 2023 report from nonprofits Education Trust and Just Equations. “This practice — and mindset — must change.”

Still, approaches school districts have taken to increase diversity in math have inspired controversy.

In San Francisco, the school district eliminated accelerated math at middle and high schools in 2014 to end the segregating of classrooms by ability, prompting parental outcry. Three years later, Cambridge Public Schools in Massachusetts began dismantling its policy of tracking students into either accelerated or grade-level math. Near Detroit, the Troy school board voted to remove advanced math for middle schools beginning later this year.

Photo by Shane Bevel (Shane Bevel for The Hechinger Report)

Similarly, the California state board of education last year adopted new curriculum guidelines that, among other ideas, encourage schools to delay algebra until ninth grade. The board insisted the framework “affirms California’s commitment to ensuring equity and excellence in math learning for all students.” But critics — including math and science professors — have suggested it does the opposite, by denying students the academic preparation they need to succeed.

“I see the value, in theory,” Rebecka Peterson, a Union High math teacher and 2023 National Teacher of the Year, said of efforts like California’s. But, she added, “Kids are so unique, and one size fits all — as a mom, it’s not what I want for my son.”

Peterson started working for Union schools about 12 years ago, teaching math classes ranging from intermediate algebra to advanced placement calculus. Early on, Peterson noticed the demographic split in her classes: “We’re a very culturally rich district, and yet, my calculus classes were mostly white,” she said.

She decided to talk with her principal at the time, Lisa Witcher. The pair discovered that, although Union High enrolled students from all 13 elementary campuses, Peterson’s calculus students primarily started at just three — the whitest and wealthiest of Union’s elementaries.

Shortly after, district administration tapped Witcher to spearhead a new early college program. She began recruiting students who had completed geometry as freshmen, but found only a tenth of Black freshmen in Union were eligible to enroll in that class. They hadn’t taken the prerequisite, Algebra 1, in eighth grade.

“That sparked some uncomfortable conversations,” said Witcher, who retired from the district in 2021.

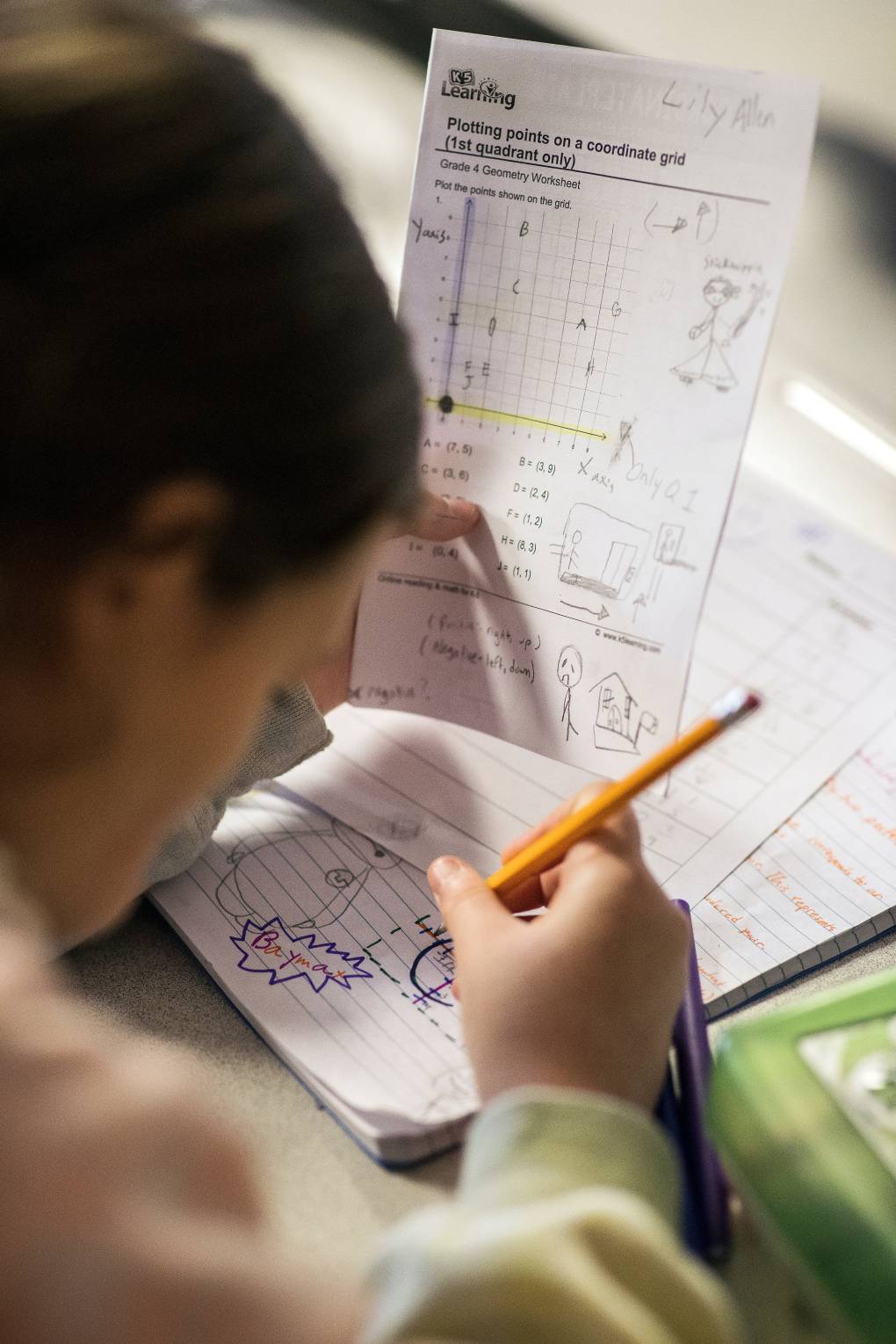

Ultimately, administrators traced the cause of the narrow pipeline into advanced middle and high school math to the fifth grade. That’s when schools administered a heavily word-based exam, which students had one chance to pass. District officials said the high-stakes exam disadvantaged two growing populations in Union schools: kids who were still learning English, and children from low-income families, whose parents couldn’t afford private tutors.

This discovery prompted a series of changes, beginning about a decade ago. The school district did not eliminate the fifth-grade exam as an entryway into advanced math, but students can now attempt the test multiple times. Elementary schools offer math tutors starting in the third grade, with after-school programs for students struggling in the subject. Teachers can refer promising students for sixth grade advanced math, regardless of how they did on the placement exam. A central administrator also reviews student grades and growth on proficiency exams to automatically enroll students into an accelerated class. (Parents are sent a letter notifying them of the automatic enrollment, at which point they can choose to opt out.)

“We hunt them down from every corner of the school district,” said Todd Nelson, a former math teacher who now oversees data, research and testing for the district.

Since 2016, the diversity of students enrolled in the district’s advanced math courses has increased. Hispanic students now make up 29% of enrollment, up from 18%; Black and multiracial students each represent 10% of enrollment, up from about 8% in 2016.

More recently, however, participation in higher-level math has dipped in Union schools, across all student subgroups. District data show the trend, especially in high school, started before the pandemic. But administrators say the disruption of school lockdowns contributed to a lingering aversion to signing up for challenging courses. Still, the share of Black, Hispanic and multiracial students enrolling in Union’s advanced math classes has fallen at much lower rates than those of Asian and white students.

“We see this as the long-term process of the work that we’re doing, as opposed to fixing the problem in one year,” Nelson added.

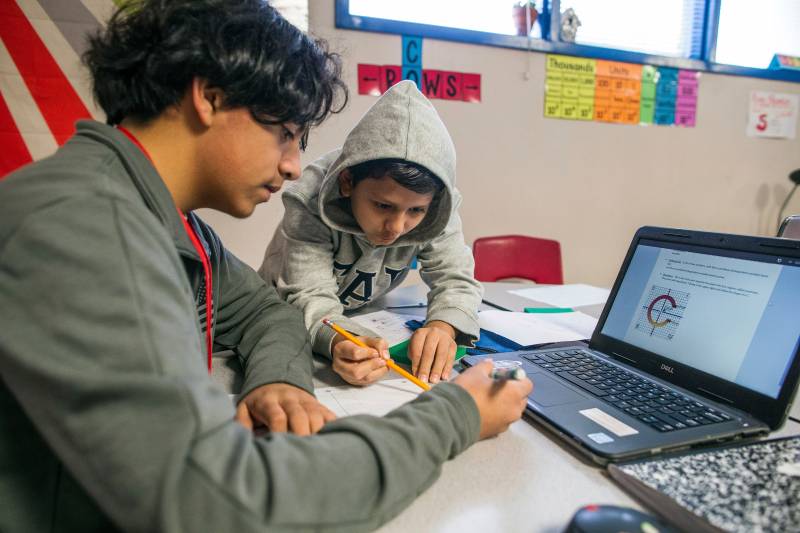

In Woodfin’s sixth grade class, 11-year-old Vianca wasn’t sure how she got into advanced math. She remembered taking a “super hard” test as a fifth grader and registered for regular math in middle school.

“I guess I was just placed in here,” she said.

Vianca said the subject has been a struggle this year. But a recent shift in sixth grade schedules to add more time for math means she has 90 minutes — instead of just 45 — with Woodfin each day.

“She always slows down” when it feels like too much, Vianca said of her teacher. “I can ask for help.”

Doubling the amount of math that both sixth graders take in Union has come with a cost. Some parents bristled at the reduction of extracurriculars, like art or music. The change required doubling the number of secondary math teachers, and principals already had a hard time recruiting teachers for those subjects. (Last school year, the turnover rate for Oklahoma teachers reached 24%, the highest rate in a decade, according to state data.)

The lack of teacher diversity also complicates the district’s overall mission of increasing diversity in advanced math, Bittle acknowledged. Only two out of about 90 middle and high school math teachers identify as Black, and efforts to recruit at Langston University, the state’s only historically Black university, have yet to prove successful. Bittle added that Oklahoma’s low pay for teachers doesn’t help: Schools in neighboring states tend to offer much more than the roughly $40,000 starting salary for teachers in the Sooner State.

Research on the detracking debate presents a complicated picture. About the same time that the district made its changes, one international study suggested steering bright students into accelerated classes could exacerbate the rich-poor divide in schools. Another paper, published by the Brookings Institution in 2016, found that Black and Hispanic students scored better on Advanced Placement exams in states that tracked more eighth graders into different ability levels in math.

“This will remain murky,” said Kristen Hengtgen, a senior analyst with the Education Trust. “Detracking seems to have good intentions, but we just haven’t seen it work conclusively yet.”

Union remains committed to its efforts, though. And in a pin-drop quiet calculus class, where only the hum of the HVAC system disrupted the scratching of pencils, students remained committed to their own hard work.

Lizeth Rosas sat in the back row. Wearing bright blue smocks for a nursing program she had later in the day, the 18-year-old scribbled notes on how to find the average value of friction with a given interval.

“Any questions?” her teacher invited. “Speak now, or forever hold your peace.”

Only eight of the 22 students in the class identified as white. Rosas first got into an advanced math as a seventh grader, she said. Last year, to her surprise, a teacher recommended she take the Advanced Placement course.

“In the beginning, I questioned myself — a lot,” she said. “I didn’t know if I was ready. It’s kind of a lot to process, and we move so fast.”

Rosas plans to work as a licensed practical nurse after graduation, and expects conversions of medications and IV fluids will require math. Her father, who runs his own remodeling company, can’t help with her calculus work, she said. But, her nursing program, part of a high school extension program at the nearby Tulsa Technology Center, offers academic tutoring.

“I don’t really need it,” Rosas said. “The teachers here are really helpful. They just kind of help me. They remind me I can do it.”