The logo of Neuralink, a brain-implant company founded by Elon Musk, superimposed on an illustration of the human brain.Credit: Jonathan Raa/NurPhoto via Getty

The first person to receive a brain-monitoring device from neurotechnology company Neuralink can control a computer cursor with their mind, Elon Musk, the firm’s founder, revealed this week. But researchers say that this is not a major feat — and they are concerned about the secrecy around the device’s safety and performance.

The company is “only sharing the bits that they want us to know about”, says Sameer Sheth, a neurosurgeon specializing in implanted neurotechnology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas. “There’s a lot of concern in the community about that.”

Threads for thoughts

Musk announced on 29 January that Neuralink had implanted a brain–computer interface (BCI) into a human for the first time. Neuralink, which is headquartered in Fremont, California, is the third company to start long-term trials in humans.

Brain–spine interface allows paralysed man to walk using his thoughts

Some implanted BCIs sit on the brain’s surface and record the average firing of populations of neurons, but Neuralink’s device, and at least two others, penetrates the brain to record the activity of individual neurons. Neuralink’s BCI contains 1,024 electrodes — many more than previous systems — arranged on innovative pliable threads.

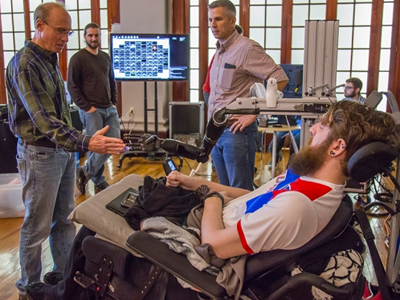

The company has also produced a surgical robot for inserting its device. But it has not confirmed whether that system was used for the first human implant. Details about the first recipient are also scarce, although Neuralink’s volunteer recruitment brochure says that people with quadriplegia stemming from certain conditions “may qualify”.

Mind over mouse

This week, Musk said on Spaces — an audio component of his social-media platform X — that the volunteer “seems to have made a full recovery, with no ill effects that we are aware of” and “is able to move a mouse around the screen by just thinking”.

To researchers working on implanted neurotechnologies, this achievement is underwhelming.

“A human controlling a cursor is nothing new,” says Bolu Ajiboye, a BCI researcher at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. The first human to receive a long-term BCI implant controlled a cursor with it in 2004 ― and non-human primates have been doing so for even longer, explains Ajiboye.

Pioneering brain implant restores paralysed man’s sense of touch

Nor are data from individual neurons needed to achieve this feat. New York City-based Synchron’s BCI, which is placed in a brain blood vessel and records the averaged firing of neuronal populations, also enables cursor control and a ‘left click’ function. And even external, scalp-based recording systems can provide users with rudimentary cursor control.

Controlling a computer mouse with one’s thoughts could enable people living with paralysis to regain some independence and functionality. But it is a far cry from Musk’s ambitions for the Neuralink device. “Imagine if Stephen Hawking could communicate faster than a speed typist or auctioneer,” Musk wrote last month on X. “That is the goal.”

Information vacuum

Implanted, high-density electrode systems developed by academic teams have enabled trial participants with paralysis to operate prosthetic robotic arms and hands, and to communicate by decoding their imagined speech. Ajiboye expects that Neuralink will soon be able to replicate some of these feats. “But it’s hard to know because there’s very little information,” he says.

Even more important at this stage, researchers say, is safety — of both the device and the surgery. Neuralink has posted online videos of its robotic surgeon sewing components of the implant into agar, Sheth says, but he and other researchers are in the dark about the system’s first application in the clinic.

Even so, scientists welcome Neuralink’s progress. “The more companies involved in human BCIs,” says Ajiboye, “the better to push the field forward.”