(RNS) — This past summer, a central issue of bioethics — brain death — came back to the fore in ways that we haven’t seen in decades, as a Uniform Law Commission committee created to update the criteria for determining when a person can be declared dead was unable to agree.

The question for many looking on was whether humans with catastrophic brain injuries count the same as more able-bodied human beings, a matter of fierce debate in itself. But what dominated the Determination of Death committee’s discussion was how a change to the criteria would inhibit organ donation by those deemed to be brain dead, even if they otherwise show signs of life.

For utilitarians, the question of justice for the individual gets subsumed into what will produce their understanding of the best consequences. Our brain death policies, in their view, are morally good if they allow us to procure more organs and save more lives. And they are morally bad if they do not.

For those who are focused more on justice, and especially justice for vulnerable individuals whose dignity is inconvenient for those with more power, considerations about consequences are deeply problematic. People with catastrophic brain injuries deserve to be treated as having full moral and legal status if that is what they are owed, period. The consequences this may or may not produce are irrelevant.

This is the understanding of justice that was at the heart of the anti-slavery and civil rights movements. The emancipation of African slaves was a matter of basic justice for a vulnerable population whose equal dignity was deeply inconvenient for those who had power over them. The civil rights movement had the same basic consideration. Those pursuing these visions of the good were not concerned with arguments coming from their opponents about the supposed bad consequences for states’ rights or for the national economy.

On the contrary, their perspective was encapsulated by the famous classical phrase: “Let justice be done, though the heavens fall!”

The current debate over how to treat prenatal human beings runs very much along these lines. More consequentialist-minded folks ignore either the question of justice for these vulnerable populations in favor of supposed consequences for women or the cost of affording prenatal children equal protection under the law.

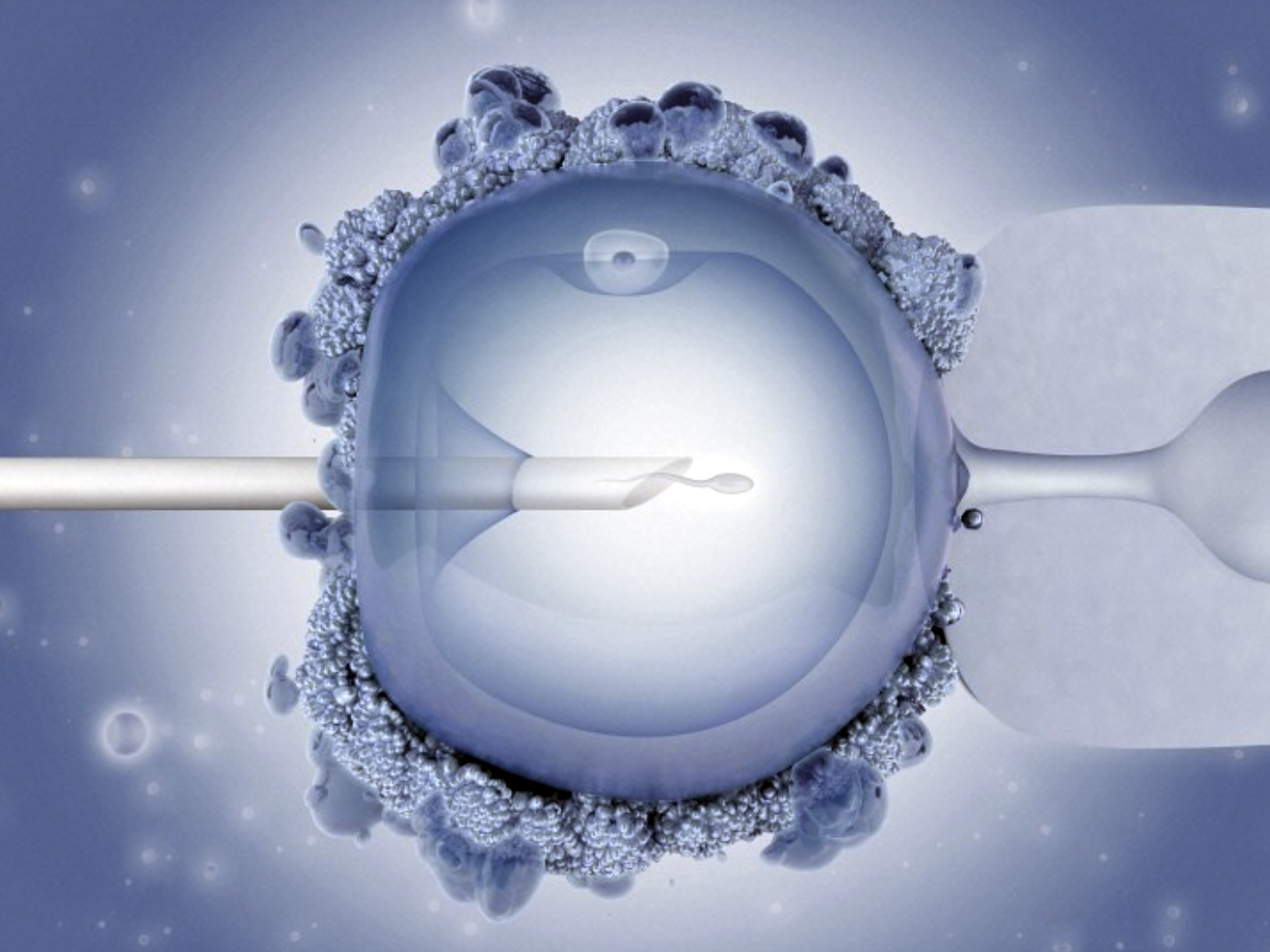

(Image by Maurizio De Angelis/Wellcome Images/Creative Commons)

Of less concern, until recently, was the effect of such equal protection on matters outside abortion, such as in vitro fertilization. A new conversation has been provoked by the recent Supreme Court of Alabama ruling that human embryos have moral and legal status as examples of vulnerable and sacred human life.

This kind of legal protection is important because, as has happened throughout the history of human injustices, the equal treatment of this helpless unborn population is deeply inconvenient for many. Under the new ruling, when human embryos in Alabama are destroyed this can now be described legally as wrongful death of a child.

Predictably, most of the objections to this ruling have focused not on the powerless population, but rather on the supposed consequences for those who benefit from in vitro fertilization. If you think that’s limited to hopeful parents, you’re not seeing the profits going to corporate biotech, which relies on massive numbers of “excess” human beings being indefinitely frozen, killed via research or simply being discarded like trash.

It would be difficult to come up with a better example of what Pope Francis describes as our technocratic “throwaway culture.”

Political opponents of the Alabama high court’s ruling have proposed legislation that transparently attempts to protect the U.S. IVF system. While the bills would insist that any fertilized human egg or embryo outside a uterus “under any circumstances” would not be considered a human being under state law, in defending his bill, Alabama State Sen. Tim Melson told AL.com that he was concerned that IVF clinics would be held liable if they accidentally destroyed frozen embryos.

Consequentialist arguments have historically been overblown, if not simply untrue. Anti-slavery and civil rights movements did not have the negative economic consequences or collapse of states’ rights predicted by their opponents.

While current American IVF practices might be put at risk by rulings like Alabama’s, it simply isn’t the case that they threaten IVF itself. Germany, for instance, has for many decades had IVF policies that don’t allow massive numbers of embryos to become a throwaway population.

But even if the U.S. way of doing IVF were the only way, offering the blessings of legal protection to vulnerable populations is something that we do for its own sake, not because it’s the most convenient.

Let justice be done, though the heavens fall.