Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

The rare species Tmesipteris oblanceolata is a type of fork fern, plants that lack true roots and true leaves.Credit: Pol Fernandez

A species of fork fern, Tmesipteris oblanceolata, has the biggest genome ever recorded. It contains 160 billion base pairs — 11 billion more than the previous record holder, the flowering plant Paris japonica, and 50 times more than the human genome. It’s not known why the plant evolved that way, or how it accesses the relatively small proportion of DNA that is actually useful. “It’s like trying to find a few books with the instructions for how to survive in a library of millions of books — it’s just ridiculous,” says evolutionary biologist Ilia Leitch, who co-discovered the giant genome.

Biomedical paper retractions have quadrupled between 2000 and 2021 — and research misconduct is often to blame. A study of more than 2,000 retractions found that issues such as data and image manipulation or authorship fraud accounted for an increasing proportion of retractions over the roughly 20-year period. It could be that research misconduct has become more prevalent, or it might just be that more is being spotted thanks to image sleuths and screening tools.

Reference: Scientometrics paper

Researchers are dropping everything to study the possibly trillions of cicadas that are emerging in the United States (Magicicada emerge periodically, and this year two 13- and 17-year broods overlap). One of the big questions scientists hope to answer is how the insects keep track of time. “There are gonna be so many graduate-student projects that we’ll have in our freezer after this year,” says entomologist Katie Dana.

Environmental engineer Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo has made history by becoming Mexico’s first female president. But just because Sheinbaum Pardo has a scientific background doesn’t mean that all researchers in Mexico are pleased with the win. Some are worried that the former mayor of Mexico City will follow too closely in the footsteps of her predecessor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who was criticized for consolidating government power over science and instituted debilitating research-budget cuts. Supporters maintain that Sheinbaum Pardo will make her own decisions. “Claudia is going to support science, and she is going to rely on science,” says biologist and campaign adviser Rosaura Ruíz Gutiérrez.

Read more: Mexico elects Claudia Sheinbaum as its first female president in landslide victory (The Guardian | 6 min read)

Features & opinion

The dyes and proteins that drive fluorescence microscopy dim over time in a phenomenon called photobleaching, which can end experiments prematurely and sometimes generates toxic by-products that can kill cells. Researchers are learning more about the chemistry that drives bleaching — or prevents it. They’re using computational simulations to optimize fluorescent properties, harnessing random mutagenesis to improve fluorescent proteins found in nature and designing fluorophores that walk the fine line between rigidity and stability.

Biodiversity researcher Luisa Maria Diele-Viegas’s lab has no fixed address, but that hasn’t stopped her from mentoring five PhD and three master’s students across Brazil. “A virtual lab format has enabled me to break from institutional constraints, allowing for greater flexibility and inclusivity,” writes Diele-Viegas. The group fosters community and connection through weekly hybrid (in-person and online) meetings, partners with other institutions to help secure funding and ships shared equipment by post so that students have equitable access to what they need.

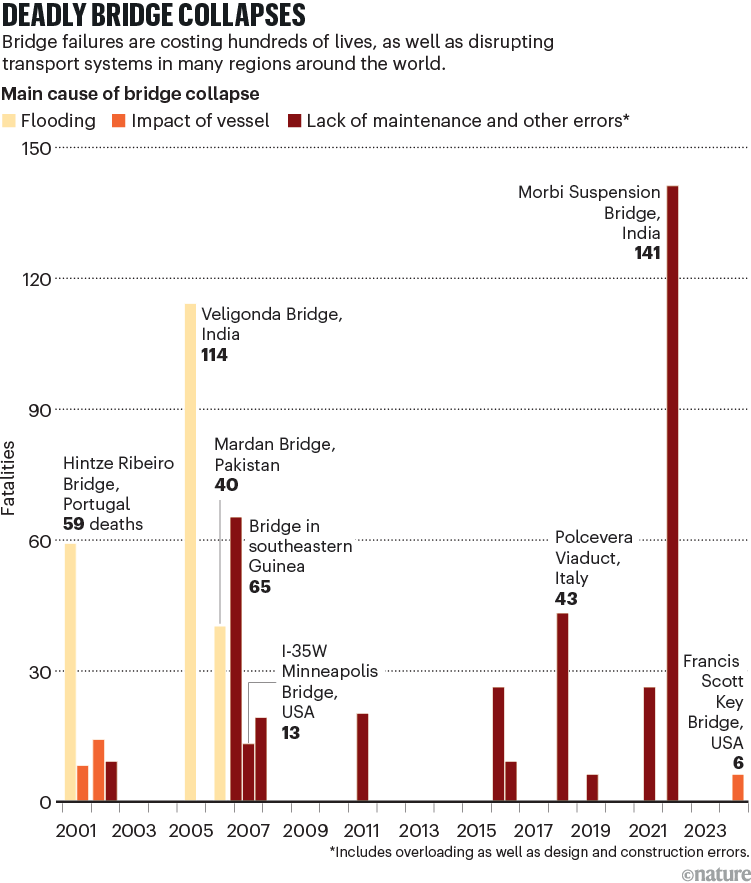

Unlike the deadly collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore in March, most bridge failures don’t make headlines. In China, for example, more than 300 highway bridges failed between 2000 and 2014, causing over 500 deaths. Hundreds of millions of people use faulty bridges every day, write four structural engineers — and climate change, poor maintenance and ageing infrastructure will only make things worse. We can learn from sectors with better monitoring and safety standards, such as aviation, argue the authors. And we need to tackle the backlog of bridge repairs — 46,000 in the United States alone.

Source: Analysis by J. M. Adam et al.

Where I work

Kristine Ulvund is a researcher at the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research in Trondheim.Credit: Lisi Niesner/Reuters

Kristine Ulvund and her colleagues at a captive breeding station for Arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus) have helped boost the population in Norway and Sweden from dozens to hundreds of animals. “In this photo, I’m crouching down helping a colleague to transfer a pup from a trap into a handling bag for a health check,” she says. “We try not to handle them more than we have to, and we prepare them as much as possible for life in the wild. As cute as they are, they are not tame.” (Nature | 3 min read) (Lisi Niesner/Reuters)

Last week, Leif Penguinson was marvelling at the rock formations in Brazil’s Sete Cidades National Park. Did you find the penguin? When you’re ready, here’s the answer.

Thanks for reading,

Flora Graham, senior editor, Nature Briefing

With contributions by Sarah Tomlin

Want more? Sign up to our other free Nature Briefing newsletters:

• Nature Briefing: Microbiology — the most abundant living entities on our planet — microorganisms — and the role they play in health, the environment and food systems.

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research — covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma