In May, millions of people were dazzled by the vibrant hues of the aurora borealis and australis — the northern and southern lights. The product of a large solar storm, curtains of green, red and purple light rippled across the night sky in regions where the spectacle is seldom seen. I saw them for the first time in the United Kingdom, from my back garden just outside Birmingham. More displays are expected in the coming months as solar activity starts to reach its peak.

But what most people didn’t see were the repercussions — and the preparations that went on behind the scenes to mitigate them. Radio communications systems experienced blackouts; Starlink, the satellite Internet provider, faced outages; and disruptions to global navigation satellite systems caused problems for sectors reliant on positioning. Meanwhile, flights were re-routed and electric grids were safeguarded.

Dazzling auroras are just a warm-up as more solar storms are likely, scientists say

This illustrates a dilemma faced by space-weather scientists such as myself: how can we issue and communicate effective warnings when even such a significant storm changes little in most people’s lives? I think part of the problem lies in how we classify space weather. Current systems are simplistic; space weather is not.

Geomagnetic storms are classified using scales developed by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in collaboration with the space-weather community. The geomagnetic storm scale (G-scale), solar radiation storm scale (S-scale) and radio blackout scale (R-scale) range from one to five, with five denoting an extreme event.

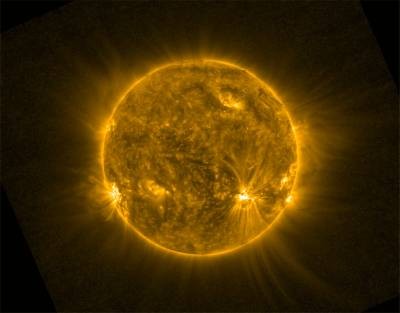

These scales have been invaluable in highlighting the risk of space weather to industries and governments, but they are due a refresh. The geomagnetic storm that caused the May auroras was classified as G5, or ‘extreme’. However, the effects of a solar storm are challenging to quantify. This storm was triggered by a rapid sequence of at least seven coronal mass ejections — massive bursts of solar matter and magnetic fields expelled from the surface of the Sun. As these collided with Earth’s magnetic field, they compressed and disturbed it, triggering geomagnetic storms.

How NASA astronauts are training to walk on the Moon in 2026

But many factors, including the speed, mass, duration and magnetic orientation of coronal mass ejections, influence a storm’s impact. In terms of peak geomagnetic activity, the May storm was a 1-in-10-year event. What set this storm apart was its prolonged duration. Geomagnetic disturbances remained high for 24 hours, making it more like a 1-in-75-year event. Auroras were visible for longer, allowing more people to witness them.

Such details make it hard to convey the risks of space weather without overstating or understating them. If an event such as that seen in May, deemed ‘extreme’, results in minimal obvious disruption, how should the risks of an even stronger 1-in-100-year storm be conveyed?

A superstorm is a looming reality. Costs could reach billions of dollars. Electric grids could be disrupted, causing local blackouts. Satellites, and the essential systems they support, could be impaired. Radio signals, crucial for aviation, maritime operations and emergency services, would be disrupted. For example, in October 2003, geomagnetic storms affected satellite communications, GPS systems and power supplies in Europe, North America and Africa.

To communicate the severity of truly extreme storms, scientists need to rethink the classification scales. Some researchers suggest extending severity levels to six and above. Others propose covering more phenomena, including the D-Scale (radiation dose rate) and the T-Scale (radio-wave propagation through Earth’s upper atmosphere).

Staring at the Sun — close-up images from space rewrite solar science

My preferred approach is to shift to a ‘traffic light’ model of warnings for specific sectors. For example, yellow space-weather warnings could alert industries, such as aviation and agriculture, that might be affected by minor geomagnetic storms. An orange warning might require users, such as power grid and radar operators, to consider taking pre-emptive action to protect their services and prepare for interruptions. A red warning would signal that dangerous space weather is expected, with potentially significant impacts requiring immediate action, and power companies, satellite operators and emergency services must implement contingency plans without delay.

Such a system would quickly alert those who should be most concerned. It could accommodate uncertainties by allowing for updates and escalations in warnings as data become available. For example, a geomagnetic event might start with a yellow warning (high impact, but unlikely) when a coronal mass ejection is first observed. It could be upgraded to orange or red if the probability of disruption increases with further modelling and data. Its reach could easily be expanded by adding sectors to the warning list.

A unified approach to refining space weather reporting and response strategies is crucial, and space weather centres worldwide must come together to discuss and agree on an updated approach. They must ensure that terms such as ‘extreme’ are not misused and that these align with events that truly warrant attention and action, and that industries and the public are adequately prepared for the real risks.

As we navigate the peak of the solar cycle, it is important to acknowledge that space weather affects our daily lives. By refining classification and reporting systems, scientists can better align public perception with reality, ensuring that we are neither crying wolf nor caught unprepared.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.