Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

The crew of Inspiration4 experience zero gravity during a practice flight.Credit: Inspiration4 crew/John Kraus

How spaceflight disrupts a person’s biology

Just a few days in orbit can cause immune-cell disruption, dehydration and cloudy thinking — but most of these conditions revert to normal soon after travellers return to Earth, according to the largest catalogue of data detailing the impacts of space travel on the human body. The reports aim to chart how spaceflight affects space tourists, who have a wider variety of health histories than trained astronauts. “This is the beginning of precision medicine for spaceflight,” says geneticist Christopher Mason, who is a co-author on some of the papers.

Reference: Nature paper 1 & Nature paper 2

The domestication of horses for the purpose of transportation happened almost a thousand years later than previously thought. A study last year credited the Yamnaya people of southwest Asia with being the first horseback riders, some 5,000 years ago. DNA analysis of 475 ancient horses now shows that it wasn’t until 4,200 years ago that horses started showing signs of human-directed breeding, including quicker reproduction and mating between closely related animals. One genetic horse lineage then quickly became dominant all across Eurasia. It’s possible that horses were first kept mainly for their meat and milk — a domestication attempt that ultimately wasn’t successful.

Reference: Nature paper & Science Advances paper (from 2023)

Chains of certain amino acids — the molecular building blocks of proteins — spontaneously form a glass when mixed with water. The cracks that form in the peptide glass when it dries out too much completely disappear when it’s left in a moist environment. What’s more, the unique properties of this peptide glass allow it to act as a strong adhesive between water-loving surfaces.

Features & opinion

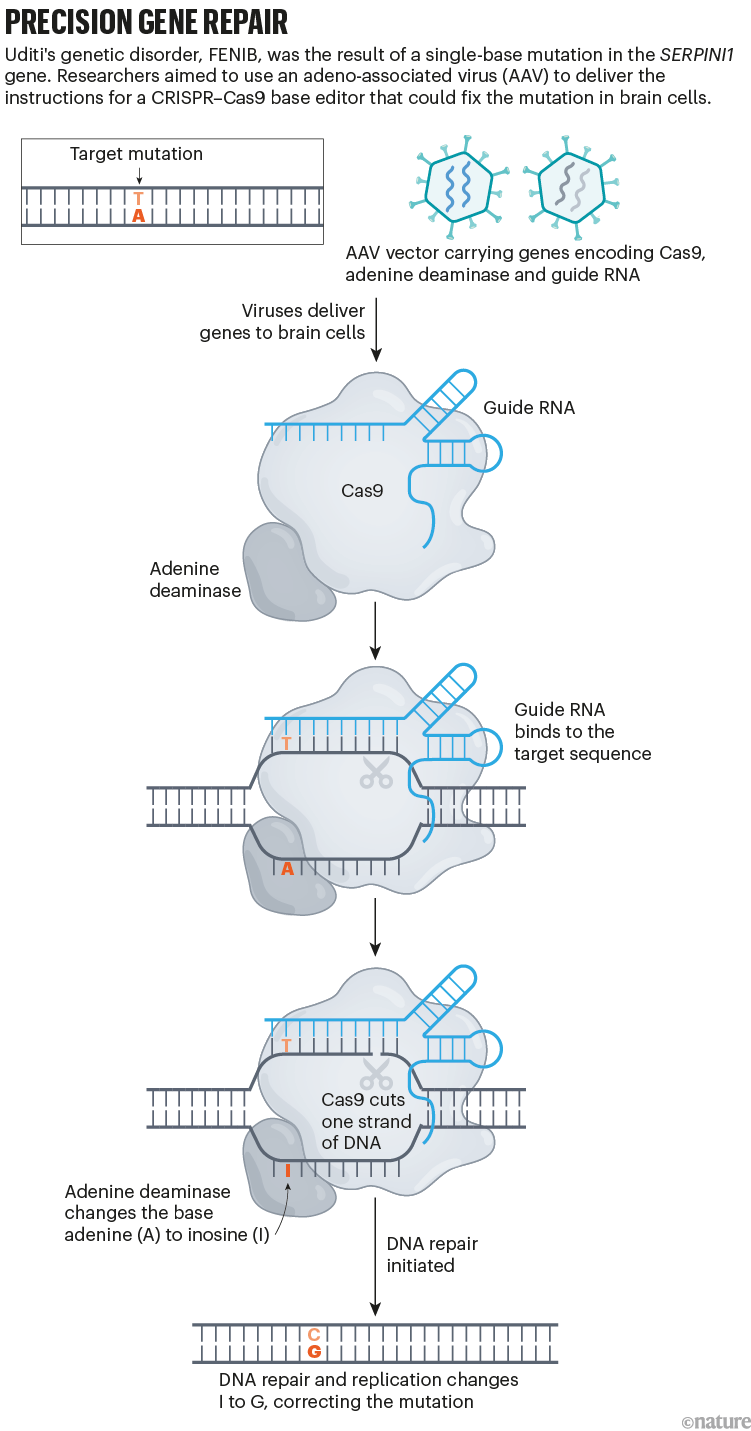

Researchers in India fought to develop what could have been the first gene-editing therapy to halt a young woman’s rare neurodegenerative disease. Ultimately, the pace of research was too slow to save her life. “What we were trying to do was really almost in the realms of science fiction,” says gene-therapy scientist Arkasubhra Ghosh. He and others remain convinced that CRISPR gene editing could offer hope to many whose genetic conditions are overlooked. “Patients are waiting, families are waiting,” says CRISPR pioneer Jennifer Doudna. “So we need to get on with it.” But the harsh reality is that it will take years to establish the techniques to quickly create bespoke therapies — time that most people with these conditions don’t have.

A restorative approach could better address the underlying problems that lead to bullying and harassment in academia. Conventional disciplinary processes, “modelled on the criminal justice system, are not fit for purpose”, says barrister Georgina Calvert-Lee. Restorative approaches — which engage all parties affected by an incident in mediated conversations — have been successfully used in other contexts, for example to tackle repeat youth offending. The process can allow people to “come to a shared understanding of what had happened and meet the needs of those individuals”, says education researcher Nicola Preston.gen

Science needs terms beyond male and female, cis and trans to capture the nuances of human gender experience, argue three scholars of bioethics and sexual health. “How people identify shapes not only their experiences of marginalization, but also their bodies — be it by influencing their smoking habits, whether they exercise, what they eat or whether they undergo hormone therapy or transition-related surgeries,” they explain. Including more than binary categories where appropriate can enhance studies’ validity, sharpen research questions and help scientists to think about what they are really trying to capture, the trio says.