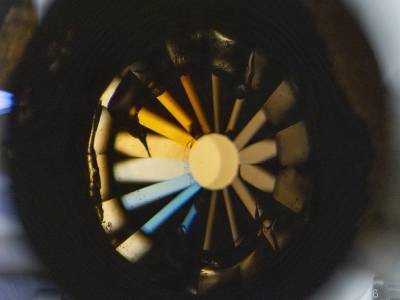

In some superconductivity experiments, a material is squeezed between two conical diamonds (one part of the apparatus shown here) to measure its properties at extreme pressures.Credit: Jan Hosan

Researchers who study high-pressure superconductors — materials that have zero electrical resistance when compressed — are once again under strain. The field is still recovering from a scandal in which physicist Ranga Dias claimed to have discovered room-temperature superconductors, but then was found by his employer to have committed extensive scientific misconduct.

Exclusive: official investigation reveals how superconductivity physicist faked blockbuster results

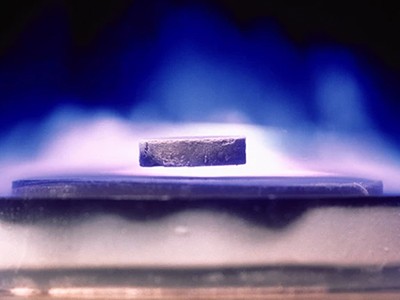

Now there are fresh concerns, this time about results from the laboratory of Mikhail Eremets, a physicist at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry (MPIC) in Mainz, Germany. In 2015, Eremets announced a stunning discovery1 that the compound hydrogen sulfide is superconducting up to 203 kelvin (–70 °C) under a pressure of 155 gigapascals — a little less than half the pressure at Earth’s centre. Most materials superconduct only at much lower temperatures; for instance, the previous record holder for the same type of superconductivity, magnesium diboride, works up to only a frosty 39 kelvin (−234 °C)2. So Eremets’s discovery was a leap forwards.

Since then, Eremets and his colleagues have continued to collect evidence about superconductivity in hydrogen sulfide and other hydrogen-based materials, called hydrides. Their June 2022 Nature Communications paper3 examined hydrides and their magnetic properties, which are crucial to materials being superconductors. That November, however, theorists Jorge Hirsch at the University of California, San Diego, and Frank Marsiglio at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada, contacted the journal with concerns, sparking a years-long dispute over data.

On 6 March this year, after Hirsch and Marsiglio raised further concerns about the paper’s data, editors at Nature Communications applied a note to the article, stating that they have been “alerted to potential problems in the manner in which the raw data have been processed”. A spokesperson for the journal says that its editors are awaiting technical feedback from reviewers, which they will use to make a decision about the paper. (Nature is editorially independent of Nature Communications.)

Superconductivity scandal: the inside story of deception in a rising star’s physics lab

Vasily Minkov, who is a lead author of the paper and also at the MPIC, told Nature’s news team that a previously undisclosed smoothing procedure had been applied to the data. He and Eremets have now performed a reanalysis without the smoothing and, on 10 August, they posted it ahead of peer review on the preprint server OSF Preprints4 along with their raw data, which weren’t previously public. They say that the raw data support the same conclusion as before: hydrogen sulfide is a superconductor.

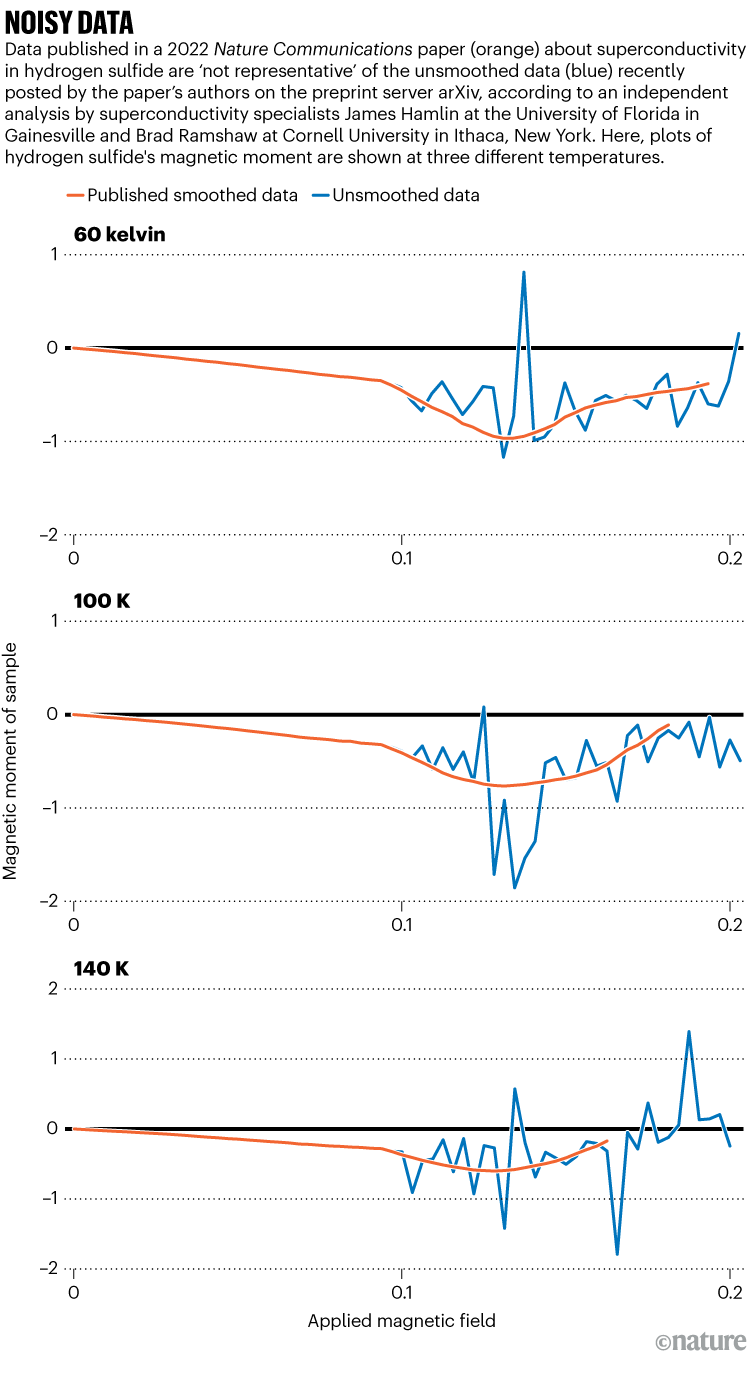

Nature’s news team asked two superconductivity specialists, James Hamlin at the University of Florida in Gainesville and Brad Ramshaw at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, to examine the raw data. They found that the data-processing procedure was so extensive that the smooth curves of the published data were not representative of the raw data, which was so noisy that it was difficult to draw reliable conclusions from. However, both agreed that there are still signs of superconductivity present. “There is overwhelming evidence that hydrogen sulfide is a superconductor, and any questions about the presentation and analysis of this specific data do not alter that,” Ramshaw says.

The dust-up over data was reported this May in the blog For Better Science. For the field of hydride superconductivity, which is still reeling from the Dias scandal, the latest dispute is not just a spat between researchers, but an existential question about how science should be conducted in a community already in turmoil.

Smoothing the way

Unlike the vast majority of condensed-matter researchers, Hirsch and Marsiglio do not subscribe to the prevailing theory that predicts that hydrides are superconductors at high pressure. If they are, Hirsch’s own theory of superconductivity would be incorrect. Hirsch was the first to flag problems with Dias’s data, and he has raised questions about many other hydride results. “Eremets and all these people accuse me that because their experiments contradict my theory, I’m out to get them,” Hirsch says. “This is nonsense.”

Why superconductor research is in a ‘golden age’ — despite controversy

Some researchers disagree. “He got the win on this Dias issue and is trying to pretend to be judge and jury for superconductivity,” Minkov says.

When Hirsch read the 2022 paper, he was struck by an inconsistency: two plots were supposed to depict the same magnetic properties for hydrogen sulfide but did not seem to match. Hirsch e-mailed the authors, but they did not respond to his questions, so he and Marsiglio submitted a comment to Nature Communications about the inconsistency. Two of the three scientists that the journal commissioned to review the comment approved publishing it, but the journal declined, and instead requested that Eremets and colleagues add a correction to the Nature Communications paper. (The comment was eventually published elsewhere5.)

The journal’s policy states that if a challenge to a paper is submitted and serves “only to identify an important error or mistake”, it will usually lead to a correction or other clarification statement.

In the correction6, published in September 2023, Eremets and his colleagues disclosed that they had subtracted a large linear background — a straight line — from one plot to create the other. Background subtractions are a common procedure in high-pressure superconductivity research to account for a large background magnetic field from the experimental apparatus, but now have a controversial history owing to the Dias scandal.

However, the correction did not answer all of Hirsch’s questions. In the original plot, the magnetic signal was not curved; in the processed plot, it was. Subtracting a straight line should never create a curve in data, Hirsch pointed out in an analysis published in January7. In May, Maarten van Kampen, a physicist who works in industry and is based in Eindhoven, the Netherlands, corroborated Hirsch’s findings, telling Nature’s news team that Eremets and his co-workers “did something” to change the noisy data into “the nice figure they published”.

Eremets and Minkov explained to the news team that they performed further smoothing. “This graph can seem misleading because it gives the impression that the lines result from averaging,” they said. “In fact, these lines are ‘guide lines’ plotted over the averaged data.”

Source: Ref. 4

Hamlin and Ramshaw had serious concerns about the validity of this data-processing method, which converted noisy raw data into smooth curves (see ‘Noisy data’). “Their procedure for obtaining the smoothed data was not described in sufficient — or any — detail” in the paper, Ramshaw says.

Minkov and Eremets defended the conclusions taken from the data — namely, that hydrogen sulfide is a superconductor — but acknowledged concerns about the smoothing procedure. “In retrospect, it is difficult to understand why we chose this kind of presentation,” they said.

Sharing practices

Much of the debate has revolved around the raw data, which Eremets declined to provide to Hirsch when asked and didn’t make public until recently.

The paper’s data availability statement says that data will be made available “upon reasonable request”. In a letter to Hirsch, Chris Graf, research-integrity director at Springer Nature in London, which publishes Nature Communications and Nature, wrote that “the authors have sufficiently explained why they have not shared their data with you”, but declined to clarify further, citing confidentiality.

How would room-temperature superconductors change science?

Eremets and Minkov say that they did not share the data because Hirsch has in the past “deliberately ignored” contradictory evidence for hydride superconductivity in his work8, which they claim is equivalent to data manipulation.

Hirsch denies this and calls the allegation defamatory. “I disagree 100% that any of my practice is unscrupulous.”

Hirsch has accused the MPIC team of violating the data-sharing policies of the Max Planck Institutes, which stipulate that data should be shared, but that exceptions can be made — for instance, if there are concerns about the misuse of data. Susanne Benner, a spokesperson for the MPIC, says that although data should generally be made available, concerns about misuse are a legitimate reason to withhold them.

Responding to a complaint from Hirsch, the Committee on Publication Ethics reviewed the case and found that Nature Communications had followed “due process”, but suggested that it clarify when requests for data are unreasonable and can legitimately be rejected. A spokesperson for Nature Communications says that the journal has updated its policy for transparency to remove the word “reasonable” so data are available only “upon request”.

Eremets says that sharing data in the superconductivity field has become fraught. “What is happening after Dias is an atmosphere of hysteria, suspicion and it’s not a community anymore,” he says. “It’s not good for science.”

Van Kampen acknowledges those fears, but says that sharing data is crucial for scientific reproducibility. By sharing data, “you make yourself vulnerable”, he says. “But I think it’s good. It is the way it should be.”