At the Center for Quantum Nanoscience (QNS), nestled in the hilly campus of Seoul’s Ewha Womans University, director of operations, Michelle Randall, shows off the facilities. “This is where we isolate our scanning tunnelling microscopes (STM) from any vibrations,” she says, pointing to an 80-tonne concrete damper, a mechanism that reduces interfering movements to near zero. Researchers at QNS are using STMs to image and manipulate individual atoms and molecules, chasing breakthroughs akin to last year’s assembly of a device made from single atoms that allows multiple qubits — the fundamental units of quantum information — to be controlled simultaneously (Y. Wang et al. Science 382, 87–92; 2023). The work, done by QNS in collaboration with colleagues in Japan, Spain and the United States, could have applications in quantum computing, sensing and communication.

What gives QNS its edge, says Randall, is the diversity of teams that populate its labs. “Our composition is 50:50, South Korean and international, and we are an English-speaking workplace as a result,” she says. “We invest heavily in building relationships with our domestic scientific community and worldwide,” she adds, pointing to one room with four women — two South Koreans, one French, and one Iranian — exemplifying the collaborative spirit.

Nature Index 2024 South Korea

The diversity of the QNS team offers a glimpse of what research looks like in a country that is betting big on international collaboration. For 2024, South Korea has more than tripled its budget for global research and development (R&D) collaboration, committing to 1.8 trillion won (US$1.3 billion), up from 2023’s 500 billion won. The investment, which represents an increase from 1.6% to 6.8% of the government’s overall R&D budget, could see a shift away from using metrics such as university rankings, quantified research outputs and international student and faculty recruitment in favour of boosting ties with leading overseas research institutions in strategic areas. “There’s a huge amount of money that has suddenly been assigned to international research. With this comes many opportunities,” says Meeyoung Cha, scientific director of the Max Planck Institute for Security and Privacy, in Bochum, Germany, who holds joint positions at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) and the Korean Institute for Basic Science, in Daejeon.

The budget increase is part of the Korean Ministry of Science and ICT’s (MSIT) wider R&D Innovation Plan, announced in November 2023. It includes a new Global R&D Strategy Map, which will guide tailored collaboration strategies with specific countries based on their strengths in 12 critical and emerging technologies, such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence (AI) and quantum science. Industry strengths in 17 technologies related to achieving carbon neutrality and mitigating climate change will also be considered. In addition, MSIT has amended laws to allow overseas research institutions to directly participate in state R&D projects and aims to develop Global R&D Flagship Projects in key areas that will receive prioritized allocation of government funds.

Such moves are designed to refocus South Korea’s R&D, which has become stagnant over the past decade, according to MSIT, despite the country being the world’s second highest spender on R&D as a percentage of GDP, after Israel. In 2023, South Korea’s legislative national assembly approved a 14.7% cut to the overall 2024 R&D budget, from 31.1 trillion won in 2023. The cuts include shifting some more general funds for universities to a separate budget.

Foreign students line up to submit their applications at a job fair in Busan, South Korea.Credit: YONHAP/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

“It seems that the term ‘budget cut’ really means redistributing money to more applied projects and international research initiatives,” says computational biologist, Martin Steinegger, based at Seoul National University. Steinegger experienced a 15–25% reduction in existing grants, paid annually from the National Research Foundation of Korea, the country’s main funding agency. This forced him to reduce conference travel for his students and use older hardware for research. “I have effectively less money than I did last year, but I can apply to many new things, it seems,” says Steinegger.

Changes could come next year, as South Korea continues to adjust its spending in science. In June, the government proposed a record 24.8 trillion won for R&D focused on basic and applied scientific research in 2025, which is up from 2024’s 21.9 trillion won, although further details were not available at the time of writing.

Global collaborator

Off the back of such policy shifts, becoming the first Asian country to join the European Union’s Horizon Europe programme, the world’s largest research-funding scheme, is a major win for South Korea. Announced in March, the new partnership will drive collaborations between South Korean and European researchers in areas such as quantum technologies, semiconductors and next-generation wireless networks. South Korea is also forging bilateral cooperation agreements across Europe, such as with Denmark on clean-energy technologies and Germany on basic sciences, including the launch of a joint centre with the Max Planck Society, Germany’s flagship basic-research organization, at Yonsei University in Seoul.

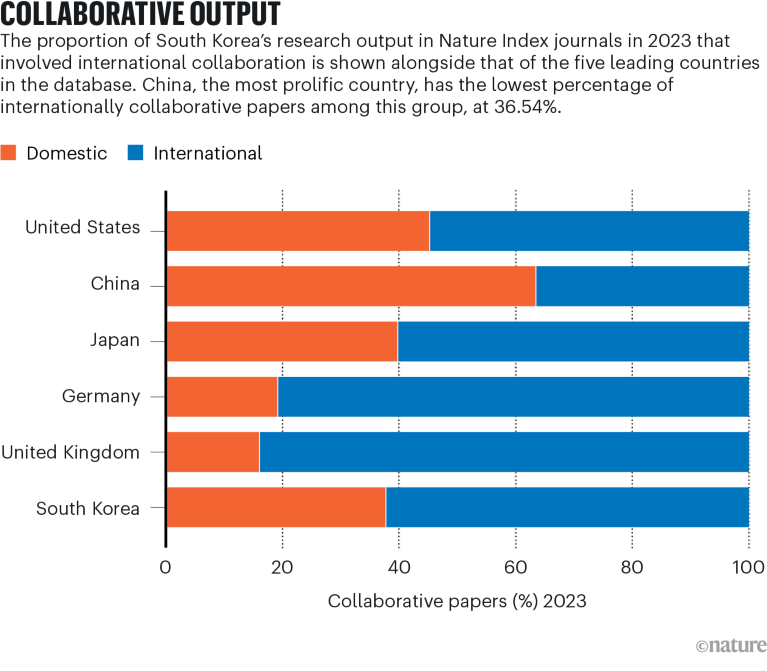

Taking on more joint projects with Europe could help to diversify South Korea’s internationally collaborative outputs in the Nature Index. The United States, which has deep historic ties with South Korea dating back to the Korean War in the 1950s, is the country’s most important research partner in natural-sciences output, with a collaborative Share — a measure of joint contribution to research tracked by the Index — of 639.94 in 2023. China forms South Korea’s second-strongest partnership, with a collaborative Share of 300.81, followed by Japan, at 114.88 (see ‘Research ties’).

The number of natural-sciences articles in the Nature Index that have been co-authored by China- and South Korea-based researchers has grown considerably in recent years, up 222% between 2015 and 2023, compared with US–South Korean output, which dropped by 4% over the same period. But South Korean researchers report that collaborations with China are becoming more difficult, particularly in technology areas. According to data from South Korea’s national police agency, of the 78 cases of industrial technology leaks recorded between 2018 and mid-2023, 51 involved leaks to places or people in China. There is now also more oversight of collaborations with China than with other major research partners. “Researchers occasionally receive requests from their institutions or the government asking who is collaborating with China, says Cha. “They are aware that any collaboration may be monitored, creating a sense of censorship.”

In order to minimize its exposure to any supply-chain disruptions or political risks associated with ongoing US–China tensions, South Korea must look farther afield when establishing research links, says Lee Myung-hwa, who studies policy and innovation at the Science and Technology Policy Institute think tank, in Sejong. “The key is building trust with collaboration partners, which needs to be long-term, stable and maintained without being swayed by policy directions,” she says.

Cha highlights southeast Asia, a region that has long been of strategic and diplomatic interest to South Korea, as a place with untapped potential for joint innovation projects. “For instance, in Indonesia, there’s no governmental institution in charge of AI,” she says, which could open up the possibility of future collaborations around ethical and strategic development of AI technologies.

In 2023, the South Korean government committed to boosting cooperation with southeast Asia in areas including cybersecurity and communications technologies, and with individual nations, such as Vietnam, to help advance digital transition and clean-energy sectors. “Huge collaboration could happen if we work together,” says Cha.

Domestic challenges

With more than 10 million visitors moving between southeast Asian nations and South Korea each year, the region could also be important to South Korea in dealing with its dual demographic challenge: attracting overseas scientists in a country that is traditionally conservative towards immigration, and retaining homegrown talent. Solving these problems is paramount, as South Korea contends with the world’s lowest birthrate, driven by factors such as the rising costs of housing, education and childcare, a highly competitive and demanding work culture, and gender inequality issues, including the biggest gender pay gap among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development members. Student numbers are also in steep decline, which is putting some universities at risk of closure. An analysis of 195 Korean universities published by Seoul-based institute Jongro Academy in March showed that 51 had failed to fill their enrolment quotas for 2024. Of those, 43 were located outside the Seoul metropolitan area, accounting for 98% of the total unfilled seats.

To boost numbers, the South Korean Ministry of Education has announced new initiatives, including annual financial support for master’s, doctoral and postdoctoral researchers. These measures, which are part of the overall R&D budget, aim to incentivize mostly local students to continue their careers in research. For foreign students, the ministry wants to attract 300,000 of them by 2027 through its ‘Study Korea 300K Project’. Students will be targeted at events and language centres abroad and science graduates may be offered an easier pathway to permanent residency and South Korean citizenship. Language proficiency requirements for admission will also be reduced. Scholarship programmes are being expanded, including the government-funded Global Korea Scholarship invitation programme, which will increase recipient numbers from 4,543 in 2022 to 6,000 by 2027. The ministry has identified India and Pakistan in particular as important sources of science and engineering talent.

It’s unclear whether efforts to attract international students will bring more of a spotlight to the challenges faced by those who are already in the country. Lewis Nkenyereye, who studies computer and information security at Sejong University in Seoul, expresses concern for the many foreign students who work part-time to satisfy the minimum bank balance requirements of their enrolments. Language barriers and administrative hurdles have led to some of them being deported for not having adequate permits, says Nkenyereye, who is originally from Burundi. “The government is aware that most foreign students have part-time jobs and should adapt its policies to better accommodate their needs,” he says.

Religious and cultural differences also pose difficulties. Muaz Razaq, a student, who left Pakistan to pursue his PhD in computer science at Kyungpook National University in Daegu, is involved in a small mosque-reconstruction project next to his university that has ignited strong opposition from segments of the local community. Razaq says he’s heard many stories from other Muslim students across South Korea who describe being taunted by their peers over food choices and who lack designated spaces for practices such as ablution before prayers.

Challenging conditions for foreign students might be contributing to South Korea’s low levels of retention after graduation. According to a 2022 report by the Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education and Training in Seoul, the number of foreign students that are earning doctorates in South Korea quadrupled in the period 2012 to 2021. But the proportion of foreign students who returned to their home country after graduation has consistently increased, from 40.9% in 2016 to 62.0% in 2021.

Source: Nature Index

It is hoped that government-funded initiatives such as the Brain Pool programme, which gives doctoral researchers access to up to 300 million won annually for three years, and Brain Pool Plus, which offers outstanding researchers with expertise in core technology fields up to 600 million won annually for up to ten years, can help to attract and retain foreign talent. MSIT also plans to introduce support programmes to help new arrivals settle in and build networks.

Recent updates to visa rules for foreign researchers and students could make it easier for universities to attract overseas talent. In July, the Korean Ministry of Justice, which oversees immigration, greatly expanded the number of universities that are eligible to recruit foreign postgraduate and undergraduate students on D-2-5 research study visas and waived the three-year work-experience requirement for international master’s and PhD holders to obtain E-3 research visas.

New opportunities

The relatively low levels of English used at South Korean universities and research institutions is a major hurdle in the country’s drive towards internationalization. The number of university courses taught in English has increased in recent years, but Korean remains the primary language of instruction at many institutions. This affects foreign researchers at all career stages because they often require help from others or full-time assistance to navigate the environment, particularly in administrative matters, says Steinegger, who can manage daily life in Korean, but needs staff to help him with paperwork.

Seoul Robotics, a company that develops AI-powered software for autonomous driving and traffic management, has mandated an English-speaking work environment to attract international talent. Such a culture is unusual in South Korea; although many companies have English-speaking requirements, these are often not enforced, says Evan Thomas, business development manager at Seoul Robotics. “The ability to communicate in English without constant translation and cultural interpretation has been a significant advantage compared to more traditional South Korean companies,” he says.

Cultural attitudes towards foreigners can also hinder long-term retention, says Thomas. “Many South Koreans view foreigners as temporary visitors rather than potential long-term residents, discouraging them from settling in,” he says. A 2023 survey by the Korea Institute of Public Administration, a government-sponsored research institute in Seoul, seems to back this up, reporting that less than half of the respondents say they accept foreign nationals as members of South Korean society.

Given the shortages of local staff that are being recorded in strategic industries such as semiconductors and AI, it’s a problem that South Korea needs to address. Another report, by the University of Science and Technology in Daejon and the Korea Industrial Technology Association in Seoul, found that just 24% of 300 South Korean companies surveyed had foreign staff. Many cited a lack of information about foreign students as the reason, suggesting that there is a disconnect between academia and industry regarding graduate careers.

Hong Bui, a student from Vietnam, accepted a postdoctoral position at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich in April, after completing her PhD at QNS. Bui cites the limited permanent career opportunities that are available to international researchers in Seoul as one of her reasons for wanting to leave, despite having a positive experience in QNS’s internationally focused environment. “South Korean companies often value overseas experience more than domestic experience, and many workplaces require Korean language proficiency,” she says.

As South Korea devotes record levels of resources to building ties with overseas institutions and attracting foreign researchers and students, its leaders hope that stronger research performance and innovation prowess will follow. But the success of such efforts hinges on the country’s ability to foster a more diverse research ecosystem, with fewer cultural challenges for foreigners to contend with.

“If the barriers are lowered and support is provided for overseas researchers to utilize South Korea’s leading research facilities and equipment, I think South Korea will become an attractive country for conducting research activities,” says Lee.