South Korea’s falling birthrate is affecting university enrolments.Credit: Seung-il Ryu/NurPhoto/Getty

South Korea is the envy of the world, by some measures. Its spending on research and development (R&D) is among the highest of all nations at almost 5% of gross domestic product, according to 2021 data. The automotive and technology giants Hyundai, Kia, LG and Samsung are household names. Science is a popular career choice — in 2021, South Korea had more researchers per million people than any other nation. And the country is home to at least one global cultural movement, K-pop.

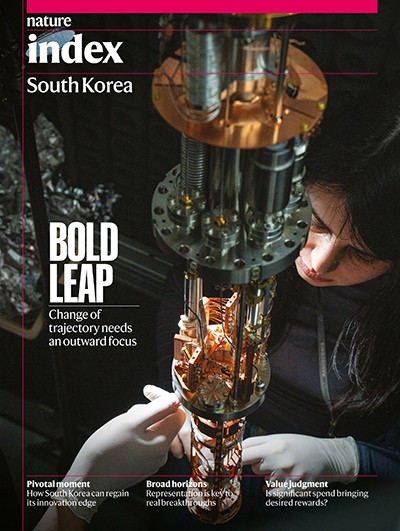

Nature Index 2024 South Korea

When it comes to research, however, it also has its share of problems, like any other nation. Gender disparity is a serious concern, says Jung-Hye Roe, a biologist at Seoul National University. In spite of policy initiatives aimed at correcting the imbalance, only around 18% of principal investigators on government-funded research projects are women. The average government grant won by a woman is worth just 41% of the average grant won by a man. That’s hurting the country, Roe writes this week in a South Korea-themed issue of Nature Index.

Another problem is that South Korea’s birth rate has been declining for decades and is now the world’s lowest, with 0.72 births per woman in 2023. As a result, prospective student numbers are projected to decline. In 2040, an estimated 280,000 young people in the country will be eligible to enter university — a 39% drop from 460,000 in 2020.

According to an analysis of higher education data by the Jongro Academy, a network of private tutoring colleges based in Seoul, 51 out of 195 universities have failed to meet enrolment targets this year. These have been dubbed ‘zombie universities’ by the national media for their low student numbers. If under-enrolment were to continue, it would represent a severe hit to both industry and academia.

Last week, a committee of advisers convened by the administration of South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol proposed a raft of ways to make research careers more attractive. Its report recommends providing more funding to cover the living expenses of science and engineering graduate students participating in government-funded R&D projects; giving early-career researchers more autonomy by allowing postdoctoral researchers and non-tenured faculty members to lead projects; and giving postdocs better employment protection in law. This last recommendation is significant, and must result in university postdocs being given the kind of career stability enjoyed by people in other professions.

South Korean scientists’ outcry over planned R&D budget cuts

Last August, the government announced plans to further boost researcher numbers by offering science postgraduate students and PhD holders from abroad a fast track to permanent residency and citizenship. And, as part of the same initiative, South Korea wants to attract more international students by 2027, bringing the country’s total to 300,000. This compares with 205,167 as of March 2023.

The government is also redirecting more of its R&D funding to international collaborations. For this year, its annual budget for such projects has tripled to 1.8 trillion won (US$1.3 billion). In March, the country sealed associate membership of the European Union’s Horizon Europe funding scheme, the world’s largest research programme. But this focus has come at the expense of funding for the kind of fundamental science that often attracts early-career researchers.

One surprising finding discussed in the Nature Index is that South Korea is not in the top tier of places where researchers easily switch between academia and industry. Researchers in Italy and the United States have more cross-sector mobility, for example. This wasn’t always the case in South Korea, however, and the COVID-19 pandemic might have played a part in weakening links between universities and industry.

Gender equality: the route to a better world

Policymakers are mindful of this and are looking at ways to boost cross-sector mobility and collaboration. The report of the government’s advisory committee, for example, proposed formally linking researchers and start-up companies, so they can solve technical challenges together.

Part of the problem is that industry-based researchers are used to projects with long lead times, so might not want to move to academia, in which the typical length of a grant is one to three years. And because academic roles are difficult to get, university-based researchers could be reluctant to risk moving to corporate jobs. The advisory committee has recommended that the government support industry-focused master’s programmes, which would run R&D projects tailored to industry needs, to train a new generation of graduates for the sector.

However, more work needs to be done to ensure that gender inequality remains at the forefront of discussions. Policymakers and their advisers must study other countries’ efforts to understand the extent of and reasons for gender gaps and discrimination, and to test solutions, such as the Athena Swan charter, an international scheme in which institutional funding has been linked to gender-equality objectives. What works in one country will not necessarily work in another, but solutions would make a material difference to researcher numbers, especially in senior leadership.

South Korea has transitioned from low-income to high-income country in a single lifetime by nurturing a highly skilled workforce. But the nation must encourage and incentivize all of its talents. Only by doing so will it continue to occupy the technological high ground.