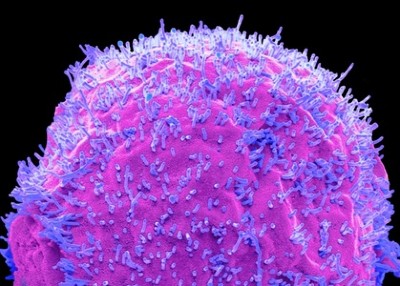

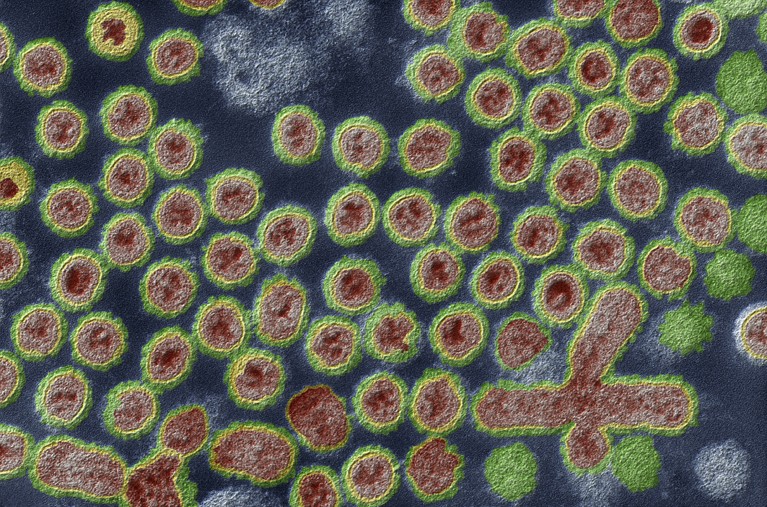

These bird flu virus particles (artificially coloured) were imaged by an electron microscope.Credit: Eye of Science/Science Photo Library

All eyes are on Missouri.

Researchers are anxiously awaiting data from the midwestern state about a mysterious bird flu infection in a person who had no known contact with potential animal carriers of the disease. The data could reveal whether the ongoing US bird flu outbreak in dairy cattle has reached a dreaded turning point: the emergence of a virus capable of spreading from human to human.

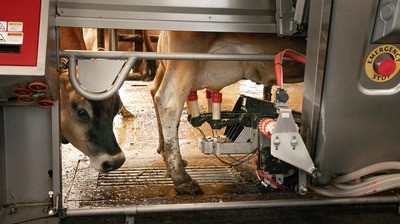

Huge amounts of bird-flu virus found in raw milk of infected cows

Thus far, data from the mysterious infection are few and far between: small snippets of the H5N1 virus’s genome sequence and an incomplete infection timeline. Ratcheting up concerns is the fact that no Missouri dairy farms have reported a bird flu outbreak; this might be because there really are no infections, or because the state does not require farmers to test their cows for the virus.

“The fear is that the virus is spreading within the community at low levels, and this is the first time that we’re detecting it,” says Scott Hensley, a viral immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia. “There’s no data to suggest that to be the case, but that’s the fear.”

A mystery case

On 6 September, Missouri public-health officials and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced that an adult in the state had developed symptoms including chest pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, and was hospitalized owing to other medical conditions. That person did not become severely ill and has recovered from the infection. Tests revealed it to be H5N1 influenza, often referred to as bird flu.

Since March, when the H5N1 virus was first detected in US dairy cattle, there have been more than a dozen cases of human infection that were traced back to contact with infected animals, including cows and birds. The Missouri case stands out because investigators found no such link and no tie to unprocessed food products, such as raw milk, from potentially infected livestock.

If bird flu sparks a human pandemic, your past immunity could help

This raised the possibility that the virus might have evolved to not only infect humans, but also to spread between people. If so, this increases the risk of it sweeping through human populations, potentially triggering a dangerous outbreak.

But that’s not the only possibility, cautions Jürgen Richt, a veterinary virologist at Kansas State University in Manhattan. “It’s a mystery case,” he says. “So you have to throw your net a little wider. Maybe they cleaned out a bird feeder in the household. Did they go to a state fair? What kind of food did they consume?”

More concerns were raised about the Missouri case on 13 September, when the CDC announced that two people who had close contact with the hospitalized person had also become ill around the same time. One of them was not tested for flu; the other tested negative.

That test result is encouraging but not definitive, says Hensley, because the sample could have been collected when the individual’s viral levels were too low for detection — after they started to recover, for instance. A key next step will be to test all three people for antibodies against the strain of H5N1 bird flu that has been infecting cattle. Such antibodies, particularly in the two contacts, would be definitive evidence of past infection.

Genomic sleuthing

While researchers await the antibody results, they are combing through patchy genome-sequence data from virus samples from the hospitalized person. This could yield any signs that the virus might have adapted to human hosts. The search is a challenge, however: the samples contained very low levels of viral RNA — so little that some researchers have shied away from analysing the sequences altogether.

Bird flu virus has been spreading among US cows for months, RNA reveals

“What I would want to see is higher quality,” says Ryan Langlois, a viral immunologist at the University of Minnesota Medical School in Minneapolis. “I am very leery about interpreting anything from partial sequences.”

But for Hensley, one feature of the sequence fragments immediately leapt out: a single change in the string of amino acids that form a flu protein called hemagglutinin (the ‘H’ in H5N1). That protein sits on the surface of influenza viruses, where it helps the viruses bind to and infect host cells. It is also a target of flu vaccines.

The change that Hensley found creates a site to which a large sugar molecule can bind. That sugar, he says, could then act as an umbrella, shielding the swath of hemagglutinin beneath it. It is a change that his laboratory has studied in other flu strains, and it could affect how the virus binds to host cells — as well as whether vaccines being developed against the H5N1 virus found in cattle can recognize and perform well against the virus detected in Missouri.

Surveillance gaps

Even if the sequences were available, researchers know little about which genetic changes might allow bird flu viruses to better infect humans or to become airborne, says virologist Yoshihiro Kawaoka at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Previous studies1,2 had suggested that changes to a gene encoding a protein responsible for copying the viral genome could be crucial for allowing the virus to replicate in mammalian cells. But researchers were unable to sequence that gene from the isolate from Missouri.

Meanwhile, the CDC has issued contracts to five companies in the United States to provide testing services for H5N1 and other emerging pathogens. Testing of cattle also needs to be improved so that public-health officials will know which regions of the country to surveil for infections in humans, says Seema Lakdawala, a virologist at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. In the United States, most testing of cattle is regulated at the state level, but only a handful of states have required routine testing on some dairy farms.

Public-health workers still don’t have a good handle on how many US herds have cows infected with H5N1, or whether cattle have immunity after contracting bird flu or can become reinfected, she says.

While researchers wait for more information, Hensley cautions against panic. “This could still be a one-off case and not the sign of something bigger,” he says.