The abnormal tissues range from black blisters to red nodules and white-hot cysts. They grow throughout the pelvic cavity, latching on to the ovaries and peritoneum or infiltrating the bowel and bladder.

Once detected, the painful lesions of endometriosis, an inflammatory condition, can be removed. But for up to half of people who opt for this, the pain returns or persists so intensely that they need surgery again within five years. “As surgeons and doctors, we want to remove lesions. But people’s pain persists more often than we like to report,” says Amira Quevedo, an obstetrician-gynaecologist who runs endometriosis clinical trials at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

The pain experienced by people with endometriosis doesn’t reflect the number, size or type of lesions present, and varies wildly between individuals. For some, the pain worsens during their period; for others, it lasts all month long. It can manifest as searing muscle spasms, or as vaginal, bowel or bladder pain that spreads across the pelvis and beyond.

Nature Outlook: Pain

This persistence of pain after the original stimuli have subsided or been removed is a key feature of many kinds of chronic pain. In some whole-body pain conditions, such as fibromyalgia, there is no clear cause. Something has tripped the pain system into overdrive, prompting a desperate search for relief.

At least in the case of endometriosis, that relief is often found in switching diets. The foods people eat can rapidly alter the vast collection of microbes that reside in the intestine, in turn releasing chemicals that either drive or dampen pain. Observations that people with chronic pain have different mixes of microbes in their gut from other individuals have also given rise to the idea that manipulating this gut microbiome — through diet or other means — might help.

That outcome remains speculative, awaiting more clinical trials. And tinkering with the microbiome is unlikely to provide relief for everyone, especially when chronic pain becomes hardwired in the brain. But given the paucity of other options, and the potential benefits, a microbiome-focused approach is worth pursuing. It could “significantly change the way we understand, diagnose and treat chronic pain”, says Amir Minerbi, a physician at the Rambam Institute for Pain Medicine in Haifa, Israel. But researchers are wary of overstating the gut microbiome’s analgesic abilities. “We don’t want to give false hope,” Minerbi says.

Gut microbes and visceral pain

The connection between the gut and chronic pain began to materialize two decades ago in studies of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a chronic condition more painful than its name suggests. IBS is marked by visceral pain, which emanates from organs in the abdomen and pelvis.

Despite decades of work probing the connections between gut bacteria and visceral pain in IBS, “it’s been a slow evolution” to recognize the gut microbiome’s role, says stress neurobiologist John Cryan at University College Cork in Ireland.

About 20 years ago, animal studies began to reveal that certain bacteria stimulate pain receptors on cells of the gut in a manner similar to morphine, among other mechanisms. In 2008, Cryan’s team showed that animals that had been stressed in early life by being separated from their mothers developed a whole-body syndrome of inflammation and sensitivity to visceral pain that was linked to changes in their gut bacteria1. “That was our first real strong look” at how changes in pain related to changes in the microbiome in an animal model, he says.

Steadily, researchers realized not only that the gut’s resident bacteria could induce persistent visceral pain — and, in fact, were required for normal visceral pain sensation — but also that transplanting certain microbes from one animal to another could relieve it. These findings have since been replicated in other types of pain, such as allodynia, a type of severe nerve pain stemming from very faint stimuli.

Human trials of probiotics have shown what Cryan says are “slight but significant” analgesic effects2 on visceral pain in IBS. Altogether, the evidence suggests that “the microbiome is playing a key role in pain”, he adds. It is even possible that gut bacteria influence not only how neurons transmit pain, but also how those acute pain signals turn chronic.

“It makes a lot of sense,” says Jessica Maddern, a pain researcher at the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute in Adelaide, who lives with the visceral and chronic pelvic pain of endometriosis. The gut is studded with nerves and constantly contacting the brain through the vagus nerve and spinal cord, she says, “so it stands to reason that it could change the way you’re experiencing pain”. Diet is already known to affect mood through the ‘gut–brain axis’, but the finer details of how gut microbiota influence pain are still being worked out.

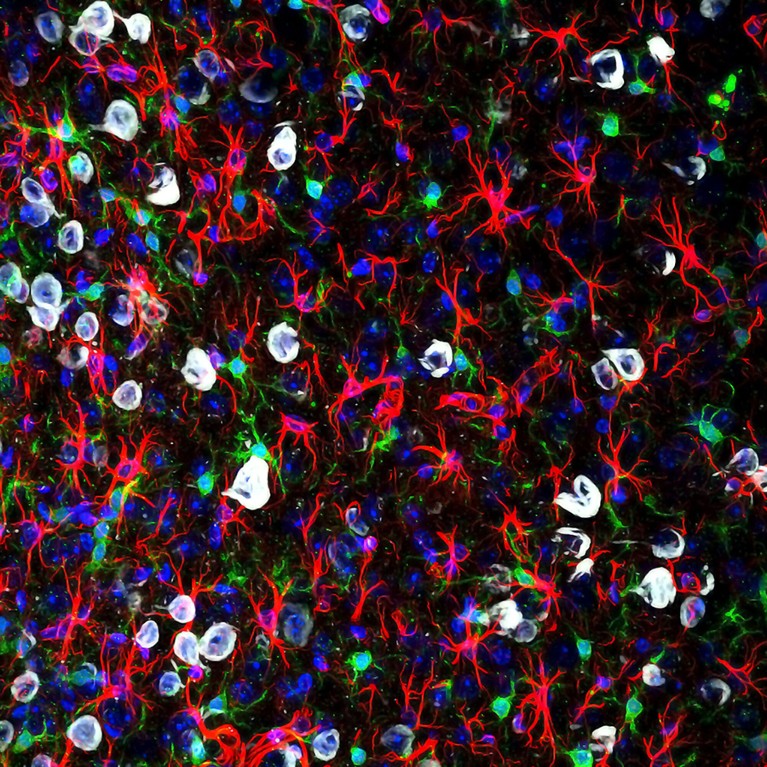

Microglia (green) can become overly reactive and affect pain signals to the brain.Credit: Gabriel Luna, NRI-UCSB/Wellcome/CC BY 4.0

Animal studies of visceral pain have identified specific chemicals, produced by gut bacteria, that can promote3 or suppress4 pain. Short-chain fatty acids, which are produced when certain bacteria digest fibre, stimulate immune cells to release pro-inflammatory factors, whereas bile acids suppress the activity of sensory nerves. The effects can be far-reaching: these metabolites can seep into the circulation through the gut lining and cross the blood–brain barrier, altering the permeability of both structures.

As a result, the gut microbiome might even influence the perception of pain. Cryan says his group’s animal studies show “very clearly” that brain regions known to be involved in the emotional and cognitive aspects of pain, such as the anterior cingulate cortex, change with alterations in the gut microbiome5. “We’re beginning to see that signals from the microbiome impinge on how visceral pain is perceived in the brain,” he says. “But we’re only scratching the surface.”

The endometriosis window

Maddern studies nerve pathways in visceral pain. Coming to this research some 20 years after her own endometriosis diagnosis, she was shocked at how little was known about pain and how to treat it. Only in the past few years have researchers begun modelling visceral pain in animal models of endometriosis, as they do for IBS. That’s because most endometriosis research has so far focused on understanding what causes the disease and the growth of lesions, rather than its pain.

Still, endometriosis — which involves interconnected and overlapping pain symptoms — could serve as a window into chronic pain more broadly. Much-improved mouse models developed by Maddern and by Kelsi Dodds, a neurophysiologist at Flinders University in Adelaide, offer fresh insights.

Maddern’s and Dodds’s work expands researchers’ understanding of the way in which pain becomes chronic, identifying how cells in the spinal cord drive a process called central sensitization. In female mice with long-standing endometriosis, the spinal cord’s resident support cells — microglia and astrocytes — amass, become overly reactive to and amplify pain signals6,7. Central pain pathways become hypersensitive to peripheral inputs, such that light touch becomes unbearable, or chronic pain persists even without any stimuli — as is common after endometriosis lesions are removed. Other researchers modelling endometriosis in mice have similarly reported swollen and therefore activated microglia in the brain8. Activated microglia are appearing in models of fibromyalgia, too9.

The anatomy of pain pathways also goes some way to explaining how the gut microbiome could affect widespread pain. Some nerve pathways innervate multiple organs in the pelvis and converge in the spinal cord, so signals from gut microbiota could very easily cross from the gut over to other pelvic organs and beyond, Dodds says.

Food for thought

Many women with endometriosis report finding relief by making changes to their diet. Some report that doing so completely changes their experience of the disease, says Francesca Hearn-Yeates, who is studying the impact of diet on endometriosis-associated pain at the University of Edinburgh, UK.

In an as-yet unpublished survey, she asked some 2,600 people with endometriosis about their symptoms, including bloating, cramps and pain, and what they ate. About 83% of respondents — drawn from 51 countries — said they had altered their diets. And of that subset of respondents, 63% said that these dietary modifications reduced their pain. No one diet stood out as the most effective, but going gluten-free and dairy-free often helped. “It’s not a fix-all for everyone,” she says, “but the fact that it’s benefiting so many people is really promising.”

To get at some of the mechanisms involved, she has begun an exploratory study to profile gut-bacteria metabolites in 50 people with suspected endometriosis who are awaiting diagnostic surgery. Multiple studies have shown that people with endometriosis have altered gut microbiomes, yet few have examined how that microbial community functions as a collective10. And relating people’s metabolite profiles to their diets and pain, as she plans to do, is new territory. “There’s clearly this really intricate interaction between the gut and the brain,” she says. But the task that looms ahead is to pin down how specific bacteria influence pain.

Therapeutic potential

Research in animals is looking to antibiotics as a way to manipulate the gut microbiome — and by extension, chronic pain. Two studies have found that metronidazole, an antibiotic used to treat gastrointestinal and reproductive tract infections, can shrink endometriosis lesions in mice11, and even stop them forming12.

This makes sense: people with endometriosis have an abundance of anaerobic bacteria sensitive to metronidazole in their gut. However, neither study looked at pain. So Quevedo and her colleagues at the University of Louisville Hospital in Kentucky are investigating whether administering endometriosis after surgery could reduce pain.

Starting in 2020, 72 people with endometriosis randomly received either low-dose metronidazole or a placebo for two weeks. The two groups showed no differences in pain six weeks after surgery13, but Quevedo remains optimistic. The trial runs until 2027, and participants will report their symptoms six months after surgery and annually for five years, a timeline more relevant to chronic pain.

However, Quevedo admits that antibiotics alone might not be enough to quell persistent pain. They could help to ‘reset’ the gut microbiome by removing problematic bacteria. But achieving a sustained benefit will probably require probiotics — which seed the gut with beneficial bacteria — along with dietary changes promoting microbial strains linked to reduced pain.

Two small randomized trials suggest that taking daily probiotics containing selected Lactobacillus strains can reduce painful periods in people with endometriosis10, but the relief seems short-lived. This transient effect probably reflects the complexity of human pain experiences compared with mouse models, Quevedo says; after enduring endometriosis for years, most individuals have persistent pain that doesn’t budge.

If clinician-scientists are to find other ways to ease pain, Quevedo says, they need to differentiate between chronic pain types and between various forms of endometriosis. This stratification of clinical subtypes is often missing from microbiome studies that lump patients together, but is necessary to work out which therapies alleviate whose pain. The same is true of chronic pain generally; pain is deeply personal and what eases one person’s discomfort might do little for someone else. “We know that one treatment is not going to help everybody,” Quevedo says.

Fibromyalgia and beyond

The role of the gut microbiome is becoming clearer in chronic pain conditions that are not visceral in origin. The foremost example is fibromyalgia, a pain disorder that typifies central sensitization — it causes widespread pain in joints, muscles and tendons, and shattering fatigue, but is often misdiagnosed.

Minerbi’s research suggests that the gut microbiome could not only help to ease fibromyalgia pain, but also aid in diagnosing it and other chronic pain conditions. In 2019, his team found that people with fibromyalgia have altered gut microbiomes, and that those slight imbalances correlated with pain and fatigue — and not with diet, medications or other environmental factors14. According to Minerbi, it was the first demonstration in humans that the gut microbiome might modulate widespread, non-visceral chronic pain.

In a 2023 study, the team found that people with fibromyalgia also had lower levels of specific bile acids in their blood compared with healthy controls15. These secondary bile acids are produced by gut bacteria that people with fibromyalgia tend to lack. In fact, the lower the level of bile acids they had circulating, the more intense pain they reported — possibly because some of these acids bind to neurons in the spinal cord that suppress pain. Without them, pain might flare unchecked. The study suggests that restoring the levels of these bile acids could help to reduce fibromyalgia pain.

Amir Minerbi prepares gut microbiome samples for analysis.Credit: Rambam Health Campus.

Minerbi and his team have tried transplanting faecal matter from healthy donors into 14 women with fibromyalgia to address such gut-microbiome imbalances. After five fortnightly treatments, 12 of the volunteers in this pilot study, which has not been peer-reviewed, reported less severe pain than before9. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial is next.

Minerbi’s group is also developing a machine-learning algorithm to relate chronic pain to gut microbiome profiles and other blood markers. So far, the tool differentiates only between people with fibromyalgia and those who do not have chronic pain14,15. The next step, Minerbi says, is to see “whether we can take someone with chronic pain and say what type of chronic pain they have, which is really the clinical question”. To that end, researchers are investigating the gut microbiome in various chronic pain conditions, hoping to find commonalities and distinct changes between them, as one 2024 study has done16.

This work has just begun. So far, most human studies have involved broad-stroke characterizations of the gut microbiomes of people with chronic pain conditions and those without. These differences — some subtle, others striking — implicate the gut microbiome in a gamut of chronic conditions, from inflammatory arthritic pain and migraine headaches to nerve-injury pain. Whether these observed differences are an underlying cause of those conditions or a knock-on effect, however, remains unclear.

Hurdles ahead

Most studies capture only a snapshot of the gut microbiome. Therefore, Cryan says, large, longitudinal studies are needed to track microbiome changes in response to symptoms and treatment. His research in animals shows that early life stress affects the gut microbiome in ways that lead to persistent visceral pain in adulthood, even though the microbiome itself recovers17. “When you’re looking at pain, the microbiome may not be a reflection of that pathology; it might be something that happened way earlier that affected pain processes,” he says.

More from Nature Outlooks

Still, Cryan thinks that modifying the gut microbiota could help to relieve chronic pain. He cites animal studies showing that specific probiotic strains can reverse well-established pain, even when given in adulthood18. That apparent plasticity offers some hope, but he says it’s essential for researchers to investigate which strains of bacteria relieve chronic pain in humans — and how long that effect lasts.

Despite these challenges, researchers are keeping an open mind that the gut microbiome could help to ease chronic pain. So immense is the burden, Maddern says, that “everything is worth trying at this point”.