(RNS) — For decades, multiple studies have shown that women are more religious than men, especially if they’re Christians. Women are more likely to belong to a congregation, pray regularly and say they feel close to God than men are.

Meanwhile, other studies have shown that until about 2010, men were more likely than women to be politically active. Other than voting, men outstripped women in every aspect of political engagement, from volunteering for campaigns to running for office themselves.

What if Generation Z is upending both of those old assumptions?

Born from the late 1990s to the early 2010s, Gen Z, also called “Zoomers,” are now in their teens and 20s. And according to political scientist Melissa Deckman, they look quite different than previous generations did at this same age.

2023 PRRI data showing the overall rate of nonreligious Gen Zers at 36%. But within that generation, the rate is higher for women than for men. (Graphic courtesy of PRRI)

For one thing, these young women are more likely to drop out of religion than men are. Several different studies from the last two years have pointed to the same surprising conclusion: After decades of men leading the way in becoming “nones,” or religiously unaffiliated, young women are now taking up that charge. In PRRI’s data, nonreligious Gen Z women outnumber nonreligious Gen Z men, 39% to 31%; in Barna’s, it’s 38% to 32%; and in a study from the Survey Center on American Life, it’s 39% to 34%.

Melissa Deckman, author of “The Politics of Gen Z.” (Courtesy photo)

Deckman, who is the CEO of PRRI and author of the new book “The Politics of Gen Z: How the Youngest Voters Will Shape Our Democracy” (Columbia University Press), says that in addition to the classic reasons why Gen Zers are dropping out of religion (e.g., that they stopped believing), there’s a political element at work as well. More than 60% of young adults who had left organized religion said they did so in part because of its poor treatment of LGBTQ individuals.

“For a lot of Gen Z women, the current intermingling of religion and politics on the political right is very unappealing because they’re more progressive on many issues, including support for LGBTQ rights and abortion rights,” Deckman said. “I think many young women see the church or organized religion as being — if not hostile, then certainly not supportive of their political values.”

As these young women witness the GOP opposing abortion rights and LGBTQ rights, and then see how deeply tied that opposition is to conservative religion, “they’re not nearly as inclined to want to go to church,” Deckman explained.

So if the first sea change is that Gen Z women are leaving religion at higher rates than young men, the second is that they’re not going quietly. They’re channeling their values into political action. The degree to which they’re doing this is new. With the millennial generation, women first closed the gender gap in political engagement, achieving parity with men. With Gen Z, though, a reverse gender gap has appeared in which young women now surpass young men’s political involvement.

Deckman’s book explores which Gen Zers are more likely to be politically involved and why. The picture looks very different from the usual story that says churchgoing evangelicals are more likely to be politically active than nonbelievers.

“Historically, political scientists who look at the relationship between political engagement and church attendance have actually found a positive correlation,” she said. Religious people have long tended to be more politically active than nonreligious people, the theory being that people might be more likely to get involved in political campaigning or community organizing if they’ve already developed social networks and social skills at church.

Deckman says that hasn’t been true for Gen Z women so far. The ones who remain involved in religion are actually less likely to be active in politics than the ones who have dropped out.

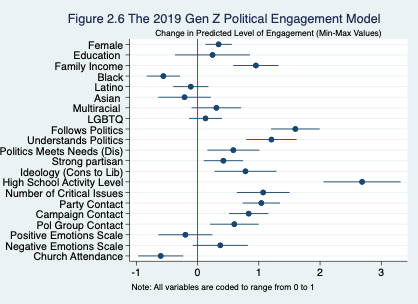

In this illustration from the book, we see on the right side of the red line which “ingredients” had an effect in catalyzing young women into political action. Some of these are no-brainers, like the fact that the most predictive ingredient is whether they were politically active in high school. Other findings echo decades of political science research, like that kids from educated, higher-income families with solid partisan identities are more likely to be politically engaged than those raised without those backgrounds.

But church attendance? That’s actually depressing political activism for this generation, especially for women.

This graphic from “The Politics of Gen Z” by Melissa Deckman illustrates the factors that contribute to political engagement for young adults, including family income, partisan ideology and high school activism. What does not predict political engagement is being religious, especially for Gen Z women. (Graphic courtesy of Melissa Deckman)

Gen Z women have taken “a very abrupt move to the left” politically, Deckman said. She cites a key Gallup study released earlier this month that shows Gen Z women as trending more liberal than young women have been in the past, particularly on issues like abortion, the environment, gun control and race relations. It used to be just over a quarter of young women who considered themselves to be politically liberal; now it’s 4 in 10, which is 15 points higher than for young men.

“Looking at trends, Gen Z women are very distinct,” Deckman said. “They’re distinct from Gen Z men, who are more ideologically moderate and diverse. But they’re also distinct from older women in that they’re openly embracing feminism.”

Related content:

This Gen Z politician wants to talk about religion more, not less

For Gen Z, crystals embed spirituality in the planet