The European Space Agency (ESA) is set to launch a mission that will assess how effective humanity could be in protecting Earth from an asteroid impact. Called Hera, the mission will visit a rock blasted by a NASA spacecraft in 2022 to analyse the effects of the deflection effort.

“It seems like we hit it hard enough and we reshaped it,” says Harrison Agrusa, a Hera team member and a planetary scientist at the Côte d’Azur Observatory (OCA) in Nice, France.

This spacecraft just smashed into an asteroid in an attempt to change its path

Hera is set to launch no earlier than 7 October on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Cape Canaveral in Florida, although the lift-off might be delayed while SpaceX investigates an issue with its launch vehicle. The solar-powered spacecraft, which is the size of a small car, will take two years to reach its target, the binary asteroid system of Didymos and Dimorphos between Earth and Mars, arriving in late 2026.

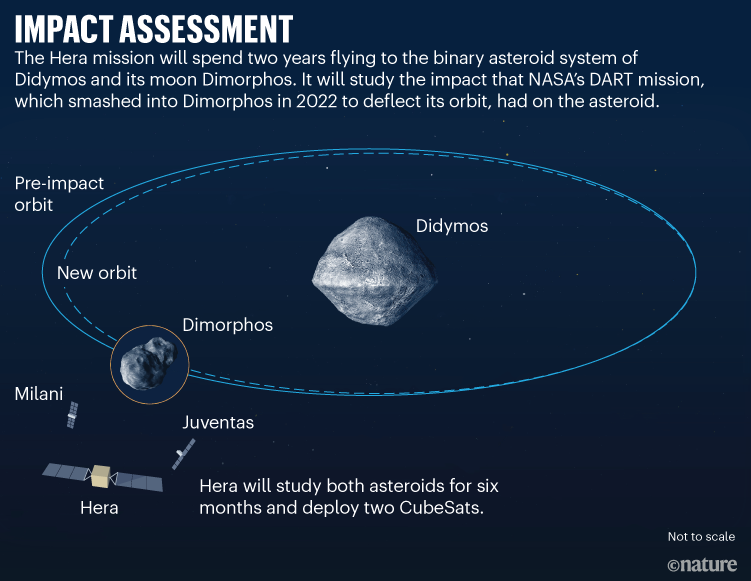

The €363-million (US$398-million) mission is a follow-up to NASA’s DART, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test. In September 2022, the similarly sized DART spacecraft slammed into Dimorphos, the smaller of the two asteroids at 160 metres across. That impact shortened the period of the asteroid’s nearly 12-hour orbit around Didymos by 33 minutes (see ‘Impact assessment’). That’s strong evidence that space agencies could, in future, use a similar approach to deflect an asteroid on course with Earth, say researchers. No such asteroid is currently known.

Delayed mission

Hera was supposed to have been present at Dimorphos for the DART impact to gather data on the experiment in real-time. But ESA cancelled the mission in 2016 before reviving it in 2019, meaning it would now arrive four years after DART. That means comparisons of Dimorphos’s form before and after impact are more difficult.

“It would have been better to have the full characteristics, but we can live with that,” says Patrick Michel, a planetary scientist at the OCA and Hera’s mission lead. “Fortunately, the outcome of the impact will [still] be there.”

Source: ESA/NASA/A. F. Cheng et al. Nature 616, 457–460 (2023).

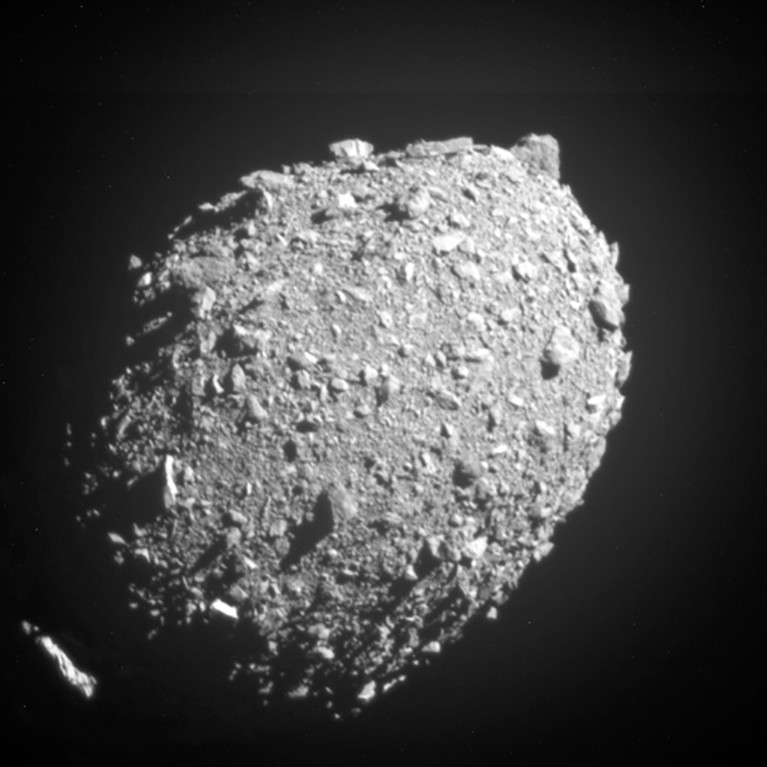

DART hit the asteroid at 22,000 kilometres per hour, and sent nearly 1,000 tonnes of material into space, including boulders the size of buses. Remote observations suggest that it formed a crater about 50 metres across, the width of a football field, but the true size won’t be known until Hera arrives. “It’s a big divot a third of the width of the body,” says Dawn Graninger, a physicist at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL) in Laurel, Maryland, and a Hera scientist.

Hera will slowly sidle up to the system when it arrives, positioning itself on a path around both rocks. “This is the first rendezvous with a binary asteroid,” says Michel. It will then study the asteroids for six months using cameras and an infrared imager, gradually lowering its altitude above them from 30 kilometres down to one kilometre.

“Hera is a detective, like Colombo,” says Michel. “It’s going back to the crime scene and telling us what happened, and why.”

Asteroid lost 1 million kilograms after collision with DART spacecraft

Reshaped asteroid

Studying the system will give us an unprecedented understanding of these two-rock systems, says Alice Quillen, an astronomer at the University of Rochester in New York. About 15% of asteroids are thought to be binaries. “One of the mysteries about binary asteroids is they’re predicted to fall apart really quickly,” she says, because of radiation pressure from the Sun. A slight wobble in Dimorphos’s orbit might explain how it stays gravitationally bound to Didymos.

It’s possible that DART’s impact reformed asteroid’s relatively spherical shape. “A lot of impact models indicate we made it elongated,” says Agrusa.

The impact might also have caused Dimorphos to tumble as it orbits Didymos. Previously, it had been tidally locked, with the same face always pointing towards its larger companion, as the Moon does Earth. But DART might have caused its axis to spin chaotically, possibly even head over heels, something Agrusa predicted before impact. “We think that this prediction might have come true,” he says.

Dimorphos as seen by the DART spacecraft 11 seconds before impact.Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL

Differences in the position of boulders on Dimorphos’s surface in Hera’s images compared with DART’s pictures could also reveal how much the rock has changed.

The mission will “tie-off some of the loose ends” of the deflection experiment, says Andy Rivkin, a planetary scientist at JHUAPL who led the DART mission and is now working on Hera.

Fresh images reveal fireworks when NASA spacecraft ploughed into asteroid

About two months into the mission, Hera will deploy two small CubeSats, called Juventas and Milani, that will encircle the asteroid pair. Measuring the distance between all three spacecraft will help scientists to work out Dimorphos’s gravitational pull and thus its mass, a crucial piece of information in understanding asteroid deflection. If the mass is low, “then maybe we deflected it so easily because it was light”, says Michel. But if the mass is high, it suggests that DART’s approach was even more effective at pushing the asteroid off course.

Both CubeSats will later attempt to land on Dimorphos, providing richer information on its gravity and composition — and take images from the surface.

Hera might also touch down on Didymos as its final resting place, ending this grand escapade. “Altogether it’s a rehearsal for if we did have to intercept something” heading for Earth, says Rivkin.