More than 200 people in Nepal were killed in floods last month, when exceptional monsoon rains inundated Kathmandu and surrounding areas. Such extreme events are becoming more common as the climate warms. But poorer nations such as Nepal are unable to call on cadres of highly trained citizens to respond.

Many Nepalese scientists, technologists, physicians, nurses and engineers are employed overseas. Each year, more than 100,000 students leave Nepal to study abroad.

I am one of them. After completing a bachelor’s degree in forestry at Tribhuvan University near Kathmandu in 2005, I moved to Freiburg in Germany to take a master’s degree, and to New Zealand for my PhD.

After several years working in New Zealand and Australia, including positions advising government and in the education sector, I’ve seen how important it is for countries to have experts on hand to protect biodiversity and manage rapid environmental change. I’ve also seen how good governance and stability are crucial for driving economic growth.

Why Mount Everest is the world’s tallest mountain

I’m keen to transfer this knowledge to the next generation of students in Nepal. So, I am starting an initiative to help the Institute of Forestry at Tribhuvan University to become a centre of excellence.

Nepal’s forests need to be managed sustainably. Strategies are needed to cope with climate change while protecting biodiversity. Carbon-credit schemes linked to forestry must be worked out. Jobs and livelihoods must be protected and improved. Ecotourism should be promoted.

Similar goals can be pursued by other diaspora scientists. According to the United Nations, about 20 million people from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are currently living in high-income nations as part of the global diaspora of workers in science and engineering.

Each year, more than one million international students are enrolled at US universities. In 2022, Canada hosted more than 622,000 international students, New Zealand around 70,000, and the United Kingdom more than 500,000. Most of these come from LMICs, especially in Africa and Asia.

Many choose to stay on, to enjoy better job prospects, higher remuneration and superior research facilities. For example, typically about 70%of students who earn PhDs in science, technology, engineering or mathematics at US universities are still in the country ten years later.

Nonetheless, ongoing connections with homelands can be beneficial. For example, expatriate researchers have played a strong part in developing the information technology sector in India, and returners have founded companies or invested in local start-up firms. China is trying to entice its citizens back by offering attractive research and development (R&D) packages. By 2020, its programmes had brought back hundreds of thousands of professionals in technology, engineering and biomedical fields.

The benefits are clear. China is now the second largest spender on R&D globally. In 2021, Chinese mainland R&D spending was more than US$440 billion , accounting for 22% of the world total. As for India, its share of global scientific publications rose from 3.3% in 2010 to 5.6% in 2019. Smaller countries can achieve similar feats. Nigeria has become a hotspot in finance and health technologies; Vietnam is becoming a hotbed of AI research.

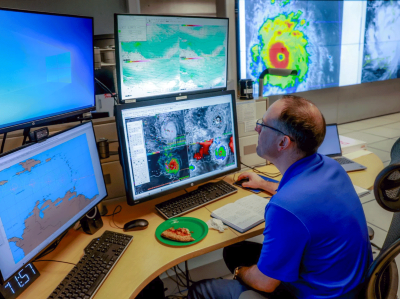

AI to the rescue: how to enhance disaster early warnings with tech tools

Nepal needs a technology revolution to create jobs and raise its gross domestic product. International partnerships can give the country’s scientists access to state-of-the-art technologies and knowledge. Digital tools and platforms can make global collaboration seamless and effective.

Expat scientists can act as bridges to build networks. On behalf of my forestry initiative in Nepal, I have reached out to institutions such as the Non-Resident Nepali Association (a diaspora network) as well as foreign universities, including the University of Technology Sydney and University of Sydney in Australia, and Dali University in China.

Nepalese students will benefit from having access to this wide pool of expertise, and research partners from learning more about the Nepalese context. Fresh thinking will lead to broader societal and policy changes in the long run.

LMICs also need more academia–industry collaboration, entrepreneurship start-up incentives and programmes to attract talent, such as China’s Thousand Talents Plan and India’s Global Initiative of Academic Networks. These will help to retain skilled people and accelerate others’ return.

To slow the brain drain, Nepal should put a quota on the number of students who can pursue a degree overseas, and limit the issuance of ‘no-objection’ certificates, a document that is currently required for studying abroad. Commitments to return after overseas study might be implemented, as Brazil has through its Science Without Borders initiative.

As well as investing in scientific infrastructure and education, LMICs should make a concerted effort to build strong, sustainable economies that can create high-income employment opportunities in the scientific sector. A political environment that is transparent and that motivates research is advantageous. Corruption should be fought, and the freedom to practise science without obstacles must be guaranteed.

Addressing the causes of the brain drain and tapping into the global diaspora can help LMICs to become the furnaces of scientific innovation.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.