As the researchers analyzed how students completed their work on computers, they noticed that students who had access to AI or a human were less likely to refer to the reading materials. These two groups revised their essays primarily by interacting with ChatGPT or chatting with the human. Those with only the checklist spent the most time looking over their essays.

The AI group spent less time evaluating their essays and making sure they understood what the assignment was asking them to do. The AI group was also prone to copying and pasting text that the bot had generated, even though researchers had prompted the bot not to write directly for the students. (It was apparently easy for the students to bypass this guardrail, even in the controlled laboratory.) Researchers mapped out all the cognitive processes involved in writing and saw that the AI students were most focused on interacting with ChatGPT.

“This highlights a crucial issue in human-AI interaction,” the researchers wrote. “Potential metacognitive laziness.” By that, they mean a dependence on AI assistance, offloading thought processes to the bot and not engaging directly with the tasks that are needed to synthesize, analyze and explain.

“Learners might become overly reliant on ChatGPT, using it to easily complete specific learning tasks without fully engaging in the learning,” the authors wrote.

The second study, by Anthropic, was released in April during the ASU+GSV education investor conference in San Diego. In this study, in-house researchers at Anthropic studied how university students actually interact with its AI bot, called Claude, a competitor to ChatGPT. That methodology is a big improvement over surveys of students who may not accurately remember exactly how they used AI.

Researchers began by collecting all the conversations over an 18-day period with people who had created Claude accounts using their university addresses. (The description of the study says that the conversations were anonymized to protect student privacy.) Then, researchers filtered those conversations for signs that the person was likely to be a student, seeking help with academics, school work, studying, learning a new concept or academic research. Researchers ended up with 574,740 conversations to analyze.

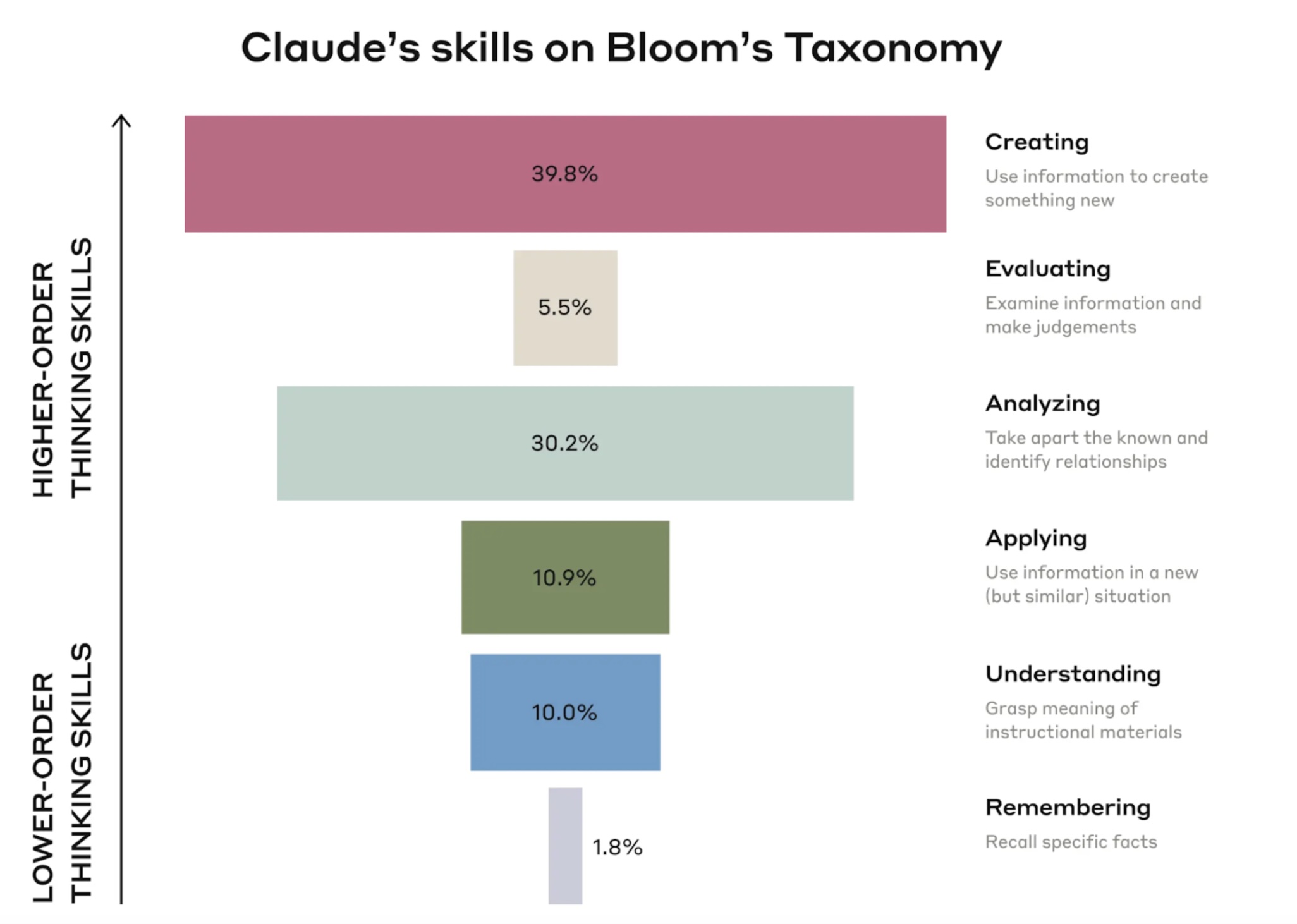

The results? Students primarily used Claude for creating things (40 percent of the conversations), such as creating a coding project, and analyzing (30 percent of the conversations), such as analyzing legal concepts.

Creating and analyzing are the most popular tasks university students ask Claude to do for them

Anthropic’s researchers noted that these were higher-order cognitive functions, not basic ones, according to a hierarchy of skills, known as Bloom’s Taxonomy.

“This raises questions about ensuring students don’t offload critical cognitive tasks to AI systems,” the Anthropic researchers wrote. “There are legitimate worries that AI systems may provide a crutch for students, stifling the development of foundational skills needed to support higher-order thinking.”

Anthropic’s researchers also noticed that students were asking Claude for direct answers almost half the time with minimal back-and-forth engagement. Researchers described how even when students were engaging collaboratively with Claude, the conversations might not be helping students learn more. For example, a student would ask Claude to “solve probability and statistics homework problems with explanations.” That might spark “multiple conversational turns between AI and the student, but still offloads significant thinking to the AI,” the researchers wrote.

Anthropic was hesitant to say it saw direct evidence of cheating. Researchers wrote about an example of students asking for direct answers to multiple-choice questions, but Anthropic had no way of knowing if it was a take-home exam or a practice test. The researchers also found examples of students asking Claude to rewrite texts to avoid plagiarism detection.

The hope is that AI can improve learning through immediate feedback and personalizing instruction for each student. But these studies are showing that AI is also making it easier for students not to learn.

AI advocates say that educators need to redesign assignments so that students cannot complete them by asking AI to do it for them and educate students on how to use AI in ways that maximize learning. To me, this seems like wishful thinking. Real learning is hard, and if there are shortcuts, it’s human nature to take them.

Elizabeth Wardle, director of the Howe Center for Writing Excellence at Miami University, is worried both about writing and about human creativity.

“Writing is not correctness or avoiding error,” she posted on LinkedIn. “Writing is not just a product. The act of writing is a form of thinking and learning.”

Wardle cautioned about the long-term effects of too much reliance on AI, “When people use AI for everything, they are not thinking or learning,” she said. “And then what? Who will build, create, and invent when we just rely on AI to do everything?

It’s a warning we all should heed.