US citizens are living a reign of terror. Trump has ordered US Marines and the National Guard to quell relatively benign street protests in Los Angeles, California, against his crackdown on immigration.

No less alarming is the number of government departments and programmes, as well as private institutions, that Trump is in the process of decimating: the Department of Education, National Endowment of the Arts, National Endowment for the Humanities, Medicaid, Harvard University (among many other institutions of higher learning), the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Health and Human Services, the Internal Revenue Service, USAID, public radio and television – the list could be twice as long.

His actions on the international stage have been equally troubling. Aside from an overinflated group of ‘deals’ that Trump has made with Great Britain and Middle Eastern countries, we’ve seen nothing more than comical boasts. Heads of state like Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelenskyy and South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa have been insulted and threatened. The wars in Gaza and Ukraine continue. And the leveraging of wildly inconsistent tariffs is forcing the rest of the world to re-evaluate its relationship to the US.

Economists are increasingly concerned that the president’s lack of economic vision will cause a recession within the next six months. Trump’s budget bill is working its way toward the Senate, with major cuts due to Medicaid, Medicare and Obamacare. Even conservative senators are complaining about how damaging these cuts would be to their constituents.

But rather than adding to the mass of articles written from impotent rage, or an analysis of the current situation as if it’s within the realm of rationality, let me offer a few summarized takeaways about the past four months under Trump.

Forget Freudian psychology

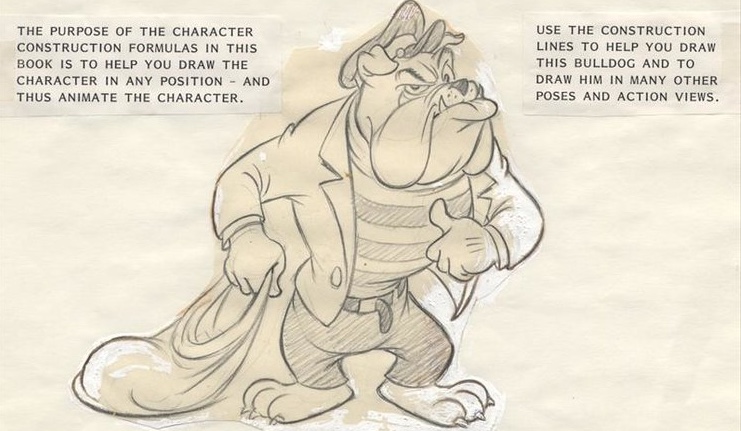

If we want to understand Trump’s behavior, we need look no further than schoolyard bullies. Trump’s swagger, his raised fist, his hissing sarcasm – all recall the square-jawed bulldogs in old Disney comics. Identifying how Trump became a bully may not be as useful as recognizing how committed he is to staying one; at 79, he still hasn’t set foot out of the schoolyard.

Original drawings of bulldog sailor by Preston Blair for Walter Foster Art Book. Image by Nemo Academy via Flickr

He picks on less powerful nations (Ukraine, Denmark, Canada, Mexico), turns meek and circumspect with countries whose leaders or wealth intimidate or impress him (Russia, China, Saudi Arabia). Like all bullies, he shies away from fights. In his first term we saw this in his timid relationships with Iraq, Syria and North Korea; the same diffidence has emerged in his vacillating behavior with Russia, Israel and Iran.

It didn’t take long for foreign heads of state to see past his bluster and find his vulnerabilities. With cameras rolling during White House visits, Canada’s Mark Karney and the UK’s Keir Starmer remained on the sidelines, let Trump puff out his chest, offered him goodies like an invitation to Buckingham Palace, and then muttered gently sarcastic remarks to let their audience know that it was all a game. This seems to be their strategy to keep him at bay.

Loneliest man in the world

Trump’s ravenous need for attention suggests he may be the loneliest man in the world. According to some reports, the first lady has separated from the president. One has to wonder whether his more outlandish proposals – like his impulse to impose 100% tariffs on all films made outside the US – pop into his head when the press is having a slow day and he feels particularly abandoned.

The press is his greatest addiction. Ten former Fox News hosts hold Cabinet-level positions in the Trump administration, including the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of Transportation and the Director of National Intelligence. A comedian recently quipped, ‘I’ve heard of state-run TV; this is a TV-run state.’

Trump grants interviews to anyone and everyone. ‘Tell the people at The Atlantic, if they’d write good stories and truthful stories, the magazine would be hot,’ he exclaimed to reporters from the Left-oriented journal during a phone interview just days after venting on Truth Social against the journal’s publisher; some of his interviews also apparently go on for days. There is something perversely generous, or rather irresponsible, about Trump’s lengthy media pursuits when the country needs governing.

In recent US presidential history, only Reagan was as comfortable with the press. But Trump is more needy. His addiction to publicity suggests that in future he’ll keep coming up with more and more outlandish ideas to keep journalists interested. Sorting out his real intentions from his flights of fancy will keep us guessing for the rest of his term.

What vision?

Trump has no comprehensive vision, at least not one that anyone is following. Beyond an isolationist, ‘deal’-oriented approach to the world, a disdain for American bureaucracy, and contempt for anyone he finds ‘foreign’, there’s nothing to latch onto. If his advisors have a vision, his mood-changes have hampered its delivery, making any philosophy unclear.

Some commentators maintain that the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 is the master plan behind the Trump administration. But even a cursory reading of the foreword to Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise with its admonition to Congress ‘to retrieve its own power from bureaucrats and the White House’ brings this notion into question; rather than returning power to Congress, Trump’s reign is focused on putting as much power as possible in his own hands.

The only guideline is Trump himself – his likes and dislikes, his experience as a businessman and entertainer, his feelings based on real or imagined slights, including rumored resentment towards Harvard because the university rejected his son.

One of the many dangers of his waffling style is the possible influence of outliers. The recent success of Laura Loomer, who convinced Trump to replace the National Security advisor, is just one instance of how vulnerable he is to influence from unvetted sources. From Rasputin to Nancy Reagan’s astrologist, history is filled with such dark figures. And Loomer is unlikely to be the last of this species that we’ll see during Trump’s term.

Impotent courts

So far, courts have failed to stem Trump’s attacks on immigrants and private institutions. Immigrants remain in high-security prisons in El Salvador, Panama, Guantanamo Bay and South Sudan. Foreign students are packing to return home. Educational institutions are shutting down dozens of research programmes. And this situation isn’t likely to get any better.

There are three major reasons for the courts’ impotence. The first is simply procedural: US jurisprudence takes time. A lawsuit has to proceed through many courts, and since the beginning of the Republic, lawyers have known how to slow the process to a crawl.

Second, with the politicization of appointed judges, appeals zigzag their way up to the Supreme Court depending on which end of the political spectrum judges represent, which slows down the process even further. Sitting presidents appoint Supreme Court justices who share their political position. Due to the split between progressives and conservatives, the Supreme Court hasn’t shown any real interest in reining Trump in and, in some instances, has even supported his disdain for the law.

The third reason seems to be a combination of timidity and fear of exposure: if the courts mounted actual resistance, their impotence might become evident. No judge has had the courage to hold Trump in contempt and demand that he complies with their decision. What power can the courts really exercise over a rogue president? They have a few officers with pistols to keep order in their courtrooms, but if a president chooses not to respect their decision, their responses are limited.

Meanwhile, the administration pays lip service to the system. It says it will comply with the law, and then continues to delay and delay.

Failed Democrat countermeasures

The only thing lower than the president’s poll ratings are the Democratic Party’s favorability ratings, which are down to a dismal 29%. Rallies, a Democratic senator’s 25-hour long speech, another senator’s futile attempt to free a deportee in El Salvador – nothing has stirred people up. Democrat voters haven’t even been particularly vocal in demanding action from their representatives.

For years, commentators said that the Democrats had lost their way, over-identifying with the Ivy League, Wall Street and identity politics. The recent publication of Original Sin: President Biden’s Decline, its Cover-up, and his Disastrous Choice to Run Again, an expose of the previous president’s administration, has only added fuel to the fire. Many Americans feel that the Democrats are as hypocritical as the Republicans, as well as being ‘elitist’ – the major political swearword of our times.

While Democrat senators and representatives have occasionally raised their voices against Trump, leaders are expending most of their energy jockeying for position to run for president in 2028. It seems like a benighted strategy. Even though Biden’s administration saw record low unemployment and passed sweeping bills addressing infrastructure and climate change, the Democrats still lost heavily in November last year. No doubt Biden’s last-minute exit was part of the problem. But failure also had to do with a lack of ideas, poor leadership and disdain for what used to be the Democrat’s base – the mainly white lower middle class that feels passed over by technology and the rapidly changing racial makeup of the country.

If the Democrats don’t find a way to re-invent themselves, their prospects for 2028 are bleak.

Missing a moral leader

Trump’s biggest ‘success’ has been the removal of morality from a government focused on winning, greed, expediency and profit. It seems clear that we’ve entered an era of blatant amorality and self-interest.

Who could re-introduce morality into politics? A courageous person to be sure – courageous to the point of seeing themselves as a martyr, because the pushback from the Right would be fierce and relentless. A charismatic person, someone who has already had a large public presence: both Barak Obama and Bill Clinton come to mind.

Whoever this person might be – and I have no idea who might emerge – there is one person in relatively recent American history – Joseph Welch – whose call to morality stopped the trajectory of a figure who disregarded the truth and lacked compassion.

Senator Joseph McCarthy was perhaps the most divisive American politician of the twentieth century. During the Cold War era of the early 1950s, he waged a campaign against supposed communists and Soviet sympathizers in many branches of the government and universities, spreading his accusations to gay people who might have been vulnerable to Soviet blackmail.

His chairmanship of the Senate’s Subcommittee on Investigations culminated in the Army-McCarthy hearings of 1954, which were intended to root out Communism in the Armed Forces; the hearings were televised and watched by millions. In an exchange with Welch, the Boston lawyer who represented the Army, McCarthy implied that a junior lawyer in Welch’s own firm had communist sympathies because he had been a member of a progressive lawyers’ association.

Welch’s rejoinder became one of the most eloquent moments in American history. ‘Until this moment, senator,’ said Welch to McCarthy, ‘I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness. Let us not assassinate this lad further, senator. You’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?’

Welch’s statement, coupled with several TV programmes by respected journalist Edward R. Murrow, proved to be the turning point in McCarthy’s career. His influence waned, he was ‘condemned’ by the Senate and died shortly afterwards.

‘Decency’ is not a word used very much in American politics today. It will take someone of Joseph Welch’s stature to resurrect the word and restore its relevance to the American debate.