Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – Archaeologists have traditionally believed that monumental architecture—large, human-constructed structures designed for visibility—was a hallmark of societies with established power structures, including social hierarchies, inequality, and organized labor forces.

Members of the Aymara community of Jachacachi work with anthropologists on Kaillachuro excavations in a region of Peru. (Luis Flores-Blanco/courtesy)

However, this perspective is being re-evaluated as new findings suggest that hunter-gatherer groups also constructed such edifices.

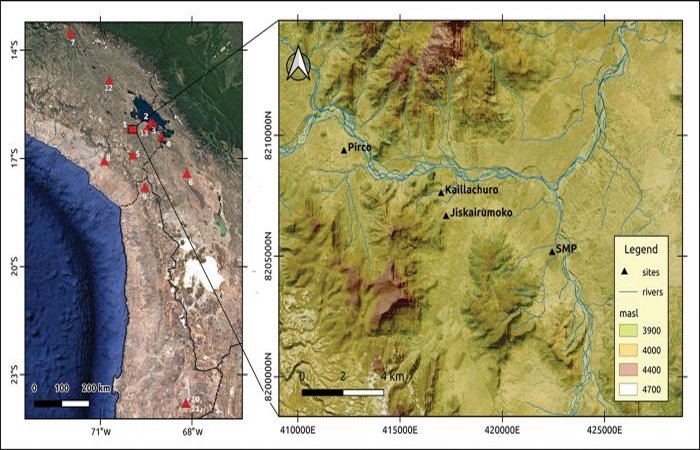

Recent research from the University of California researchers reveals evidence of monumental structures created by hunter-gatherer communities at Kaillachuro, located 3930m above sea level), on the highest terrace in the middle Ilave drainage of the Lake Titicaca Basin in southern Peru.

The site, discovered during a pedestrian archaeological survey in 1995, comprises burial mounds located in the Titicaca Basin of the Peruvian Andes. The discovery suggests that monumental architecture appeared in this region 1,500 years earlier than previously believed.

“Most researchers in the Andes argue that monumental architecture is a product of elites, intentionally constructed as a space of centralized power,” said the study’s corresponding author Luis Flores-Blanco, who conducted the research while a doctoral student in anthropology at UC Davis.

“We propose that monumentality can emerge from hunter-gatherer groups without institutionalized inequality.”

The locations of Late Archaic/Terminal and Early Formative sites. Credit: Antiquity (2025). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2025.40

A study, co-authored by Mark Aldenderfer, a professor emeritus of anthropology and heritage studies at UC Merced, indicates that the ritual memory of the deceased significantly contributed to the development of monumental architecture in the region.

Now, researchers believe that burial practices initially started on a modest scale with basic pits dug into the ground.

Over time, these practices evolved into the construction of stone masonry burial boxes that were eventually covered by mounds of debris resulting from ongoing rituals and remembrances of the community’s ancestors.

Initial excavation of Mound 4 in the late 1990s; b) the view, looking south-east, of Mound 6 prior to any archaeological intervention (figure by authors). Source

The sites at Kaillachuro were constructed over 2,000 years ago. Using radiocarbon dating, researchers suggest that these mounds represent the earliest evidence of monumental architecture in the Titicaca Basin, with construction dating back approximately 5,300 calendar years to the present day. This is 1,500 years earlier than monumental architecture was previously thought to have existed in the region.

“Kaillachuro is an extraordinary find because it shows that mounds were used in ritual contexts for over 2,000 years — though not necessarily continuously,” said Flores-Blanco, who is now a postdoctoral researcher at Arizona State University. “Our study shows that rituals surrounding the dead can, through repeated action, generate visible monumental formations in the landscape.”

Kaillachuro, identified in 1995 by Aldenderfer, comprises nine low-lying mounds. Comprehensive surveys and excavations revealed human burials and stone tools, such as projectile points, alongside various other artifacts.

Researchers propose that the construction of Kaillachuro began when egalitarian hunter-gatherer communities began to settle permanently. This settlement facilitated population aggregation, rudimentary food production, expanded exchange networks, and the advancement of bow-and-arrow technology.

“In this way, Kaillachuro was not initially planned as a mound site, but rather developed gradually through ongoing acts of burial ritual and remembrance tied to the community’s ancestors,” Flores-Blanco said.

The study presents an alternative approach to mounded architecture. It focuses on community and the ritual remembrance of the deceased rather than traditional societal power structures.

In this context, the memory of the dead transcended symbolic representation and became a tangible architectural form.

According to Flores-Blanco, “in many cultures, burying ancestors encourages us to revisit, reflect, and designate a space as significant.”

At Kaillachuro, similar practices occurred—these repeated actions created mounds that not only altered the landscape but also likely impacted living practices. This construction method, deeply embedded in communal memory, is what renders it monumental.

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer