Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – Historians have long debated the origins and spread of Slavic material culture and language, questioning whether it was due to a mass migration, the gradual assimilation of local populations, or a combination of both. The evidence has been sparse, particularly in the early centuries when cremation practices hindered DNA studies and archaeological findings were limited. However, a new study utilizing ancient DNA is poised to illuminate these critical questions and reveal how Slavs transformed Europe.

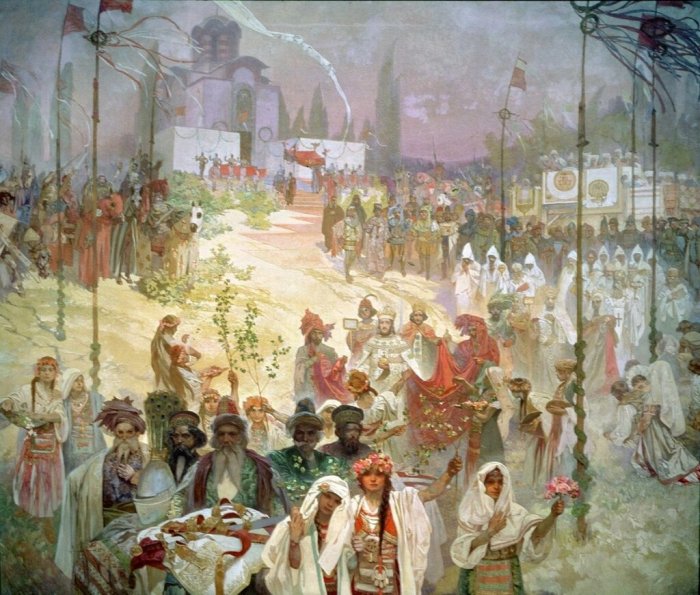

The Slav Epic – The coronation of the Serbian Tsar Stefan Dušan as East Roman Emperor. Credit: Public Domain

The expansion of the Slavs is one of Europe’s most significant yet least understood historical events. Beginning in the 6th century CE, Slavic groups started appearing in Byzantine and Western records as they settled across vast regions from the Baltic to the Balkans and from the Elbe to the Volga. Unlike well-documented migrations such as those of Germanic tribes like the Goths or Langobards or legendary conquests by groups like the Huns, understanding Slavic history has posed challenges for medieval European historians.

This difficulty arises partly because early Slavic communities left minimal archaeological evidence: they practiced cremation, constructed simple dwellings, produced plain pottery without decoration, and did not create written records for several centuries. Consequently, even defining “Slavs” has been complex—often applied by external chroniclers or misused in later nationalistic debates.

To address these uncertainties about their origins and impact on Europe’s cultural landscape, an international team led by researchers from Germany, Austria, Poland, Czechia, and Croatia under the HistoGenes consortium has conducted a groundbreaking, comprehensive ancient DNA study on medieval Slavic populations.

Through the sequencing of over 550 ancient genomes, the research team has uncovered that the emergence of the Slavs was fundamentally a narrative of migration. The genetic evidence indicates their origins in a region extending from southern Belarus to central Ukraine. This finding aligns with previous linguistic and archaeological reconstructions, which have long proposed this geographic area as the cradle of Slavic development.

“While direct evidence from early Slavic core regions is still rare, our genetic results offer the first concrete clues to the formation of Slavic ancestry—pointing to a likely origin somewhere between the Dniester and Don rivers” says Joscha Gretzinger, a geneticist from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig and lead author of the study.

Beginning in the 6th century CE, data indicate that large-scale migrations spread Eastern European ancestry across Central and Eastern Europe, significantly altering the genetic composition of regions like Eastern Germany and Poland. Unlike traditional models of conquest and empire, these migrations were characterized by flexible communities rather than sweeping armies or rigid hierarchies. Societies were often organized around extended families and patrilineal kinship ties.

The burial site of an adult woman, undisturbed and intact, reveals genetic markers that suggest she was a local resident. Accompanying her remains were grave goods, including jewelry made from glass beads and an amulet crafted from a cowrie shell. Pre-Slavic cemetery of Brücken, feature 13913:29. Credit: Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte

In Eastern Germany, this shift was particularly pronounced; society was anchored by large, multi-generational pedigrees with extensive kinship networks that differed from the smaller nuclear families of the previous Migration Period. Conversely, in areas such as Croatia, the influx of Eastern European groups caused minimal disruption to existing social structures. Here, communities often retained features from earlier periods, allowing new and old traditions to blend or coexist.

This regional diversity underscores that the spread of Slavic groups was not uniform but a dynamic transformation tailored to local contexts and histories.

“Rather than a single people moving as one, the Slavic expansion was not a monolithic event but a mosaic of different groups, each adapting and blending in its own way—suggesting there was never just one “Slavic’ identity, but many.” explains Zuzana Hofmanová from the MPI EVA and Masaryk University in Brno, Czechia, one of the senior lead authors of the study.

Spotlight on eastern Germany

The genetic record provides fascinating insights into historical migrations, revealing no significant sex bias as entire families moved together, with both men and women playing equal roles in shaping emerging societies. Future data will further illuminate how each community adapted to migration and its local history.

In Eastern Germany, the genetic data tell a particularly compelling story. After the decline of the Thuringian kingdom, over 85% of the region’s ancestry traces back to new arrivals from the East. This represents a shift from the earlier Migration Period when populations were more cosmopolitan, exemplified by Brücken—a late antique cemetery in Sachsen Anhalt showcasing Northern, Central, and Southern European ancestry.

Excavation in 2020 at the pre-Slavic cemetery of Brücken, Mansfeld-Südharz District (Saxony-Anhalt). Credit: Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte

As Slavic groups spread, this diversity transitioned to a population profile similar to modern Slavic-speaking communities in Eastern Europe. Archaeological evidence from cemeteries indicates these new communities were organized around large extended families with patrilineal descent patterns; women typically left their home villages upon marriage to join other households.

Today, this genetic heritage persists among the Sorbs—a Slavic-speaking minority in Eastern Germany—who have maintained a genetic profile closely linked to early medieval Slavic settlers despite centuries of cultural and linguistic changes surrounding them.

Spotlight on Poland

In Poland, recent research challenges previous notions of long-term population continuity. Genetic evidence indicates that from the 6th and 7th centuries CE, the region’s earlier inhabitants—descendants with strong ties to Northern Europe and Scandinavia—largely vanished and were gradually replaced by newcomers from the East. These newcomers are closely related to modern Poles, Ukrainians, and Belarusians. This conclusion is supported by analyses of some of Poland’s earliest known Slavic inhumation graves at Gródek, offering rare direct evidence of these early migrants. Although the population shift was significant, genetic data also show minor instances of intermixing with local populations. These findings highlight both the magnitude of population changes and the intricate dynamics that have shaped today’s Central and Eastern European linguistic landscape.

Spotlight on Croatia

The Northern Balkans exhibit a distinct pattern compared to other northern immigration areas, characterized by both change and continuity. Research into ancient DNA from Croatia and surrounding regions indicates a notable influx of Eastern European-related ancestry, yet this did not result in a complete genetic overhaul. Instead, Eastern European migrants intermingled with the region’s diverse local populations, forming new hybrid communities. Genetic studies reveal that in contemporary Balkan populations, the proportion of Eastern European ancestry varies significantly but typically constitutes about half or less of the modern gene pool. This underscores the area’s intricate demographic history.

Aerial view of the Velim burial site in Croatia. Credit: Archaeological Museum Zadar

At Velim, one can observe this mixed community formation where some of the earliest Slavic burials display evidence of both Eastern European migrants and up to 30% local ancestry. The Slavic migration here was not marked by conquest but rather by gradual intermarriage and adaptation. This process has contributed to the cultural, linguistic, and genetic diversity that continues to define the Balkan Peninsula today.

Independent confirmation in Moravia, Czechia

In a recent study published in Genome Biology, researchers from Czechia, Germany, Switzerland, and the UK, led by Dr. Zuzana Hofmanová, discovered a significant population change in Southern Moravia (Czechia). This demographic shift is linked to the emergence of Slavic-associated material culture originating from modern-day Ukraine. The study found that while earlier Migration-period individuals exhibited considerable genetic diversity, those associated with Slavic cultural horizons showed genetic affinities to Northeastern Europe—a trait not previously observed.

The dataset notably included an infant buried within an early Slavic context typically associated with cremations. This finding helps pinpoint the regional and temporal changes tied to the Prague-Korchak culture. Furthermore, this genetic signal persisted through individuals from the 7th and 8th centuries and continued into the 9th and 10th centuries when this area became part of one of the earliest Slavic states—the Moravian principality. This period is notable for Saints Cyril and Methodius’ contributions to creating Old Church Slavonic language and Glagolithic script for their mission among the Moravian Slavs.

A new chapter in European history

This study not only solves the historical enigma of how one of the world’s largest linguistic and cultural groups emerged but also sheds light on why Slavic groups expanded so effectively, leaving few traces historians traditionally sought. According to medievalist Walter Pohl, a senior lead author of the study, the Slavic migration exemplifies a unique model of social organization: “a demic diffusion or grassroots movement, often in small groups or temporary alliances, settling new territories without imposing fixed identities or elite structures.”

Their success likely stemmed from a pragmatic and egalitarian lifestyle that avoided the burdens and hierarchies prevalent in the declining Roman world. In many regions, Slavs presented a viable alternative to surrounding waning empires. Their social resilience, simple subsistence economy, and adaptability made them well-suited for periods of instability caused by climate change or plagues.

New genetic findings support this view. Where early Slavic groups appear in archaeological and historical records, their genetic traces align: they share common ancestral origins but exhibit regional differences due to mixing with local populations. In northern areas where earlier Germanic peoples had largely departed, space was available for Slavic settlement. In southern regions, Eastern European newcomers integrated with established communities. This patchwork process accounts for today’s remarkable diversity in cultures, languages, and genetics across Central and Eastern Europe.

See also: More Archaeology News

Johannes Krause from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology states that “the spread of the Slavs was likely the last demographic event on a continental scale to reshape both Europe’s genetic and linguistic landscapes permanently.” With these findings, researchers can now look beyond gaps in written records to trace the true extent of Slavic migrations—one of Europe’s most influential yet understated historical chapters—echoes of which persist today in languages, cultures, and even DNA across millions on the continent.

The study was published in Nature

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer