Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – While excavating at the cemetery of Nowy Chorów in northern Poland, archaeologists made an unusual discovery and found evidence that graves were reopened during the Middle Ages.

Why would people bury the dead if the graves would later be reopened and the remains cremated? What role did the three-headed Slavic god Triglav play in these funerary rituals? These were the questions Polish archaeologists sought to answer as they examined the Orzeszkowo-type (rectangular) burial mounds and both inhumation and cremation graves.

Pomerania’s location along the Baltic Sea and river networks made it a key gateway to Central Europe during the Early Middle Ages (AD 800–1100). As the Piast state, Poland’s first historical ruling dynasty, rose around AD 950, Pomerania became a hub for cultural and political exchange among the German Kingdom, Scandinavia, the Baltic region, and Rus.

Distribution of cemeteries with Orzeszkowo-type mounds (drawn by T. Drozdowski & S. Wadyl). Credit: Wadyl et.al. 2025 / Antiquity

The tenth to twelfth centuries saw significant changes in politics, religion (especially Christianity), the economy, and society. While Western Pomerania’s Christianization is well documented, records for Eastern Pomerania are scarce, except for brief mentions, such as St. Adalbert’s mission in AD 997. This lack of documentation makes archaeology crucial to understanding this pivotal period in Pomeranian history. The recently excavated cemetery at Nowy Chorów provides valuable insights into the past, as well as people’s beliefs and traditions.

Cemetery In Nowy Chorów – A Place Where Christianity And Paganism Co-Existed

Due to the scarcity of written records from this era, archaeology plays a vital role in uncovering the history of Pomerania during a transformative period. The recently excavated cemetery at Nowy Chorów provides important evidence about past societies, shedding light on their beliefs and traditions.

Nowy Chorów, a small town, is home to a well-preserved cemetery situated deep within a forest and far from major settlements. The graveyard has largely remained untouched. In 2022, spatial analysis and lidar surveys identified 16 earthen mounds organized into two distinct clusters. The western cluster features 10 mounds aligned along a north–south axis, while the eastern cluster comprises seven mounds arranged in a less regular pattern. Non-invasive geophysical investigations indicate that these mounds contain internal divisions, likely representing individual graves. Because much of the cemetery remains undisturbed, archaeologists can study local burial customs in detail.

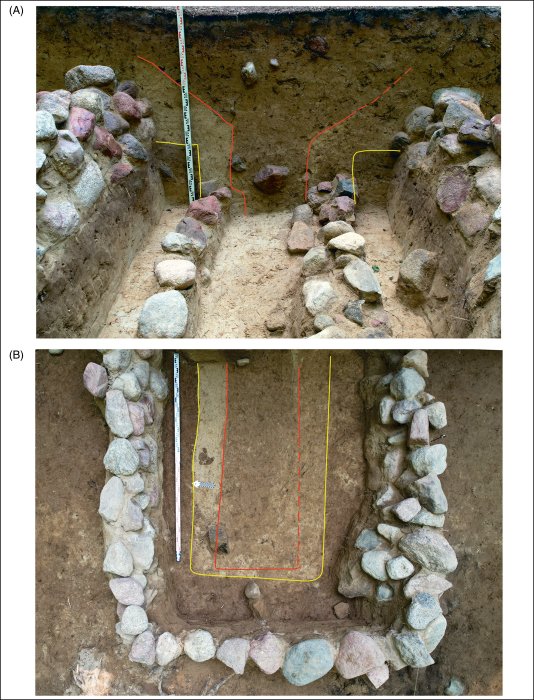

Grave 7 showing the original grave cut (yellow line) and later intrusive cut (red line); A) is a cross-section; B) a plan of the grave. Credit: S. Wadyl, Antiquity, 2025

Research at Nowy Chorów began anew in 2022 under the leadership of Dr. Slawomir Wadyl from the University of Warsaw’s Faculty of Archaeology and Dr. Pawel Szczepanik from Nicolaus Copernicus University’s Institute of Archaeology. Their primary objective is to analyze how the cemetery was organized, examine various burial practices found there, and interpret these findings within the broader context of Christianization in the region.

Excavations have revealed that many mounds contain multiple burials. For instance, mound K8 held eight graves: six were traditional burials (inhumations) while two involved cremation. The graves themselves varied widely—from simple pit graves or those marked by single stone rings to an impressive central grave (grave no. 7) featuring double stone enclosures measuring up to 5.2 by 3.6 meters.

Excavations initiated in 2022 focused on mound K8, where archaeologists discovered eight burials: six inhumations and two cremations. The cremation graves were identified as simple pit burials, whereas the inhumation graves displayed a range of forms, including basic pit burials, single enclosures, and more complex double enclosures. Among these, grave 7 stood out for its central location and substantial size—measuring 5.2 by 3.6 meters—and was marked by a prominent double-stone setting.

All burials were oriented along an east–west axis, with the head to the east. This arrangement contrasts with traditional Christian burial customs, which typically position the head to the west so that individuals face the rising sun on the Day of Resurrection. The difference in orientation suggests that these burial practices may reflect a transitional or syncretic phase that incorporates elements from various cultural or religious traditions.

Unique Artifacts Discovered Among The Grave Goods

The Nowy Chorów graves contain a variety of equipment typical of the 11th century. Common finds include iron knives, often in leather sheaths with fittings, as well as ornaments and accessories such as temple rings—decorative items worn by women—and belt buckles. Notably, a single silver coin was discovered: a cross-shaped denarius from Saxony dating to the transition between the 10th and 11th centuries, which helps confirm the site’s chronology.

Artifacts from Grave 7: an iron spearhead with textile remnants and a reconstructed yew bucket with iron banding. Credit: J. Szmit, 2025, Antiquity, 2025

Among these finds, the central grave in barrow K8 (grave 7) stands out as likely belonging to a person of high status. Although evidence suggests this grave was plundered, it still contained unique artifacts, such as an iron spearhead with traces of fabric—possibly from a pennant or banner—and a wooden yew bucket reinforced with iron bands. Such symbolic and elite objects are rare in early medieval cemeteries and highlight the exceptional significance of the individual buried there.

Biritualism And The Re-Opening Of Graves

The re-opening of graves is a practice documented in various regions across Europe, but evidence for this phenomenon in early medieval Poland has been limited. The findings at Nowy Chorów mark the first well-documented instances of grave reopening in this area, suggesting that such practices may have been more widespread than previously recognized.

In these cases, the two reopened graves initially contained inhumations, with the deceased likely buried according to Christian customs—such as east–west grave orientation and minimal grave goods. Subsequently, at an undetermined time after burial, the bodies were exhumed and subjected to cremation.

Journey To The Afterlife And The Symbol Of The Three-Headed God Trivlav

Archaeological findings indicate that the introduction of Christian burial customs did not immediately replace older pagan cremation traditions. In both ancient and medieval times, reopening graves and interacting with the dead was considered a hazardous act, necessitating special rituals. Evidence such as three-armed stone symbols discovered in two burial mounds points to connections with the triquetra, the number three, and the underworld. These symbols may be linked to Triglav, a three-headed god worshipped by the Pomeranian Slavs and described in medieval chronicles as a deity of heaven, earth, and the underworld.

In funerary contexts, these symbols could represent not only a merging of the worlds of the living and dead but also an integration of ancient beliefs with emerging Christian practices. Similar motifs appear in artifacts like those from Zbruch River dowry sites and an eleventh-century fitting from Oldenburg. The presence of such symbols in burials likely reflects pre-Christian beliefs intended to offer protection or balance against Christian rites.

See also: More Archaeology News

Each burial mound at Nowy Chorów provides unique insights into early medieval funerary practices. The differentiation observed during Pomerania’s Christianisation reveals that ritual changes were more complex than a simple shift from paganism to Christianity; rather, they reflect nuanced cultural transitions.

Future research will focus on identifying who was buried within these graves—whether specific lineages were interred together or if more intricate patterns exist. Ancient DNA analysis holds promise for answering these questions. Ongoing investigations at Nowy Chorów are expected to shed further light on early medieval burial customs at this site and throughout the Baltic region.

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer

Expand for references

Janusz Krzysztof Kozlowski, Kazimierz Godlowski – Historia starozytna ziem polskich

Wadyl S, Szczepanik P, Fetner R, Jaskulska E, Nowosadzka I. Nowy Chorów Project: funerary practices associated with rectangular burial mounds in early medieval Pomerania. Antiquity. 2025;99(407):e43. doi:10.15184/aqy.2025.10142