(NEW YORK) — The Tenement Museum in Manhattan’s Lower East Side kicked off a “Lived Religion” series on Sunday (Sept. 22) by immersing visitors into the High Holiday celebrations and shared apartments of 20th-century Eastern European Jewish immigrants.

The tour is the first in a series that will help visitors understand religious traditions and holidays outside houses of worship and, instead, inside homes and neighborhoods. Part of the museum’s aim is to elevate stories of past immigrants, migrants and refugees at a time when the country is divided over immigration policy.

“I just hope people think about what it’s like to be a newcomer in a city, in a city like New York, that has so many pulls,” said Annie Polland, president of the Tenement Museum. “What it’s like for individuals, for families and communities to think about how to re-create their holidays and their holiday calendar here in New York.”

During the 10 days that begin with Rosh Hashana and conclude with Yom Kippur, those in the tenement apartments refocused their individual concerns to the concerns of the collective, solemnly seeking forgiveness from others and from God, Polland added.

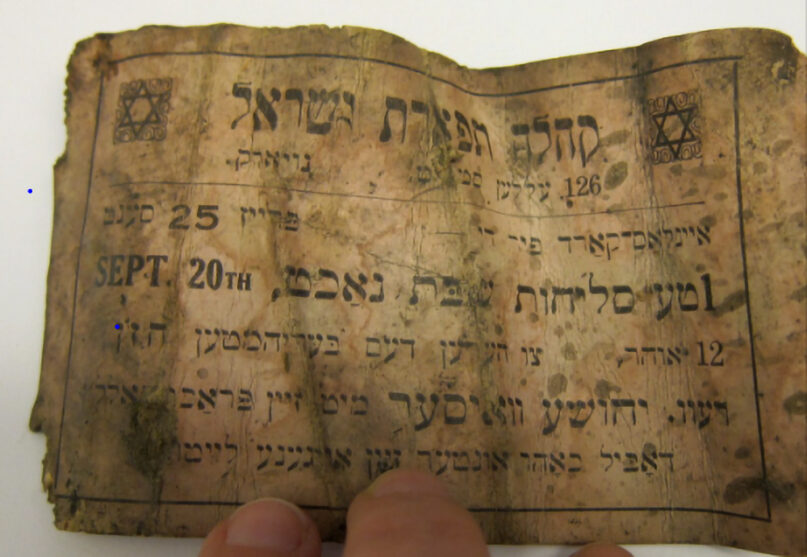

The idea for the tour was inspired by museum staff finding a pair of High Holidays tickets from 1908 under the floorboards of one of its tenements.

A 1908 High Holiday ticket found by Tenement Museum staff in New York City. (Photo courtesy of Tenement Museum)

At the turn of the 20th century, the Lower East Side hosted a large Yiddish-speaking Jewish community. More than 400 synagogues operated inside rented spaces such as movie theaters and dance halls. The tour explores the tension of how Jewish immigrants adapted to life in New York, including the workweek, and how women in particular kept religious practices alive in their families, including through food.

Over the High Holidays, the tenements’ Jewish families sipped chicken soup, sang music of the cantor and baked challah. Food historian and special guest to the museum Sarah Lohman provides a cooking demonstration on the tour, drawing from the first Yiddish cookbook, published by Hinde Amhanitski in 1901.

“There are food items that are passed down through a family that it would not be the holidays unless you made it,” Lohman said. “It’s one of the times where assimilation fails in some ways, that we manage to maintain our cultural heritage around these holidays.”

Visitors taste Lohman’s citron cake, a modern version of one of Amhanitski’s recipes, to symbolize something sweet in place of the traditional apples or honey to celebrate Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year. Using etrog, the recipe also incorporates a nod to Sukkot, which comes after the High Holidays.

The tours are limited to 30 visitors to keep the experience as intimate as possible, according to Kathryn Lloyd, vice president of programs and interpretation at the Tenement Museum.

Throughout the fall, the museum will host tours, tastings and talks, including “Lived Religion” programs for Christmas, Lunar New Year and Ramadan. The goal is to have visitors ponder common themes such as collective responsibility and forgiveness, Lloyd said.

Annie Polland, right, leads a “Lived Religion” High Holidays tour at the Tenement Museum in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Sept. 22, 2024. (RNS photo/Genevieve Charles)

While the next High Holidays tour Sept. 29 is sold out, a virtual tour on Oct. 29 will highlight a hidden magical economy on the 19th-century Lower East Side and how immigrant women such as a famous palm reader influenced America’s interest in Spiritualism at that time.

In December, a Christmas in Kleindeutschland tour will be held every weekend and will explore new research from 1870s German newspapers and the stories of local German immigrant saloon owners to show how debates over Christmas celebrations helped shaped their national identities in the U.S.

“This fall we look forward to offering New Yorkers and visitors from across the country dynamic opportunities to engage with personal migration stories that shine light not only on diverse cultural traditions, but the patterns of history and the way in which the migrant experience is fundamental to what it means to be an American,” Polland said in a statement.