Credit: Adapted from Getty

When the job of department chair became available in 2009, Glenn Geher decided to take on the challenge. “Partly, I thought I would be good at it, and partly, I was not super-satisfied with the department the way that it was,” he remembers.

“This was my third academic job, and at one of the jobs I’d had an incredibly well-functioning psychology department,” he says. Geher, a behavioural scientist and founding director of evolutionary studies at the psychology department at the State University of New York in New Paltz, thought that the lessons in management he’d learnt in that previous post could really be of benefit.

Administrative roles, such as heads or chairs of departments or posts such as dean, are crucial for the functioning of universities. Terms for these management positions typically last three or four years, and their holders often undertake consecutive terms. In these roles, they provide leadership and strategic direction for the department or faculty; oversee the budget; hire people and deal with internal disputes, among other tasks. Researchers take on these roles for a variety of reasons. Many wish to serve their colleagues or make changes to the way in which their department or faculty is run; others want to raise their professional profile or gain administrative experience.

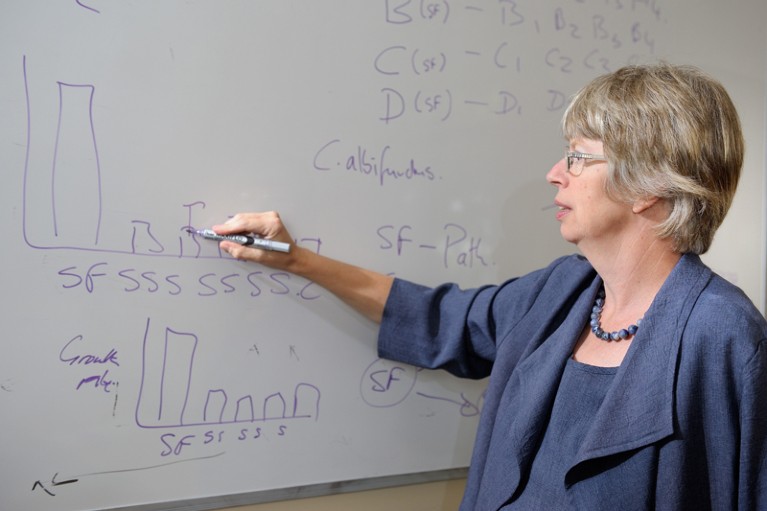

Following her time as department chair, education scholar Teboho Moja has taken a sabbatical to refocus on her research.Credit: Ben Ouriel/New York University/Steinhardt

Several studies have shown that having top scholars at the helm of a department improved its research output1 and its faculty members’ job satisfaction2. Good researchers “know what needs to be done”, says Brenda Wingfield, a plant geneticist at the University of Pretoria, who took on the role of deputy dean of research at her institution for eight years. “I mean, how can some idiot who doesn’t know research tell me about my career?”

But researchers who put up their hand often struggle to balance the bureaucratic demands of administration and their research programme — and sometimes they give up research altogether. There are several steps that scholars can take to ensure that their research survives a stint in administration, say those who have done it. One key thing to remember: “Research is not a tap that you can switch on and off,” says Wingfield.

Make research time sacred

The most crucial tool is what Geher calls “holy time”, which was time he set aside for engaging with students and for research meetings. His group “met at a very specific time, always at 4 p.m. on a Friday, and that meeting time did not get cut into. It became as important as my office hours or a meeting with the dean or provost.” Part of the reason that holy time was effective for him was that he felt beholden to his students and colleagues and did not let other duties override his obligations to them. “Having the research meeting with students means you have to do the research, because you’re responsible to this group of people,” says Geher, who held the post of department chair from 2009 to 2017.

Wingfield also fenced off time for research. On Fridays, she commandeered the dean’s boardroom for the day and used it to meet with students and research colleagues. Without this sacred, set-aside time, researchers interviewed say that they would have struggled to keep up with their research.

Team science content collection

“It’s incumbent on these great researchers who are going to go into these roles to say, I need to negotiate time for my research during that period,” says Amanda Goodall, a leadership researcher at the Bayes Business School, City University of London, who has studied university management and scholarly output. When in discussions with their universities about taking up a new administrative role, academics need to take the initiative and ensure that research time is built into it.

In fast-moving fields, such as computer science, it is tricky to keep up with the latest developments, warns Mark Wass, a computational biologist at the University of Kent in Canterbury, UK, and head of its School of Biosciences. He acknowledges that his research has slowed since he took on the role. “You see all these exciting developments and you want to capitalize on them, but you don’t really have the time to go off and investigate them or think about the research we could do.”

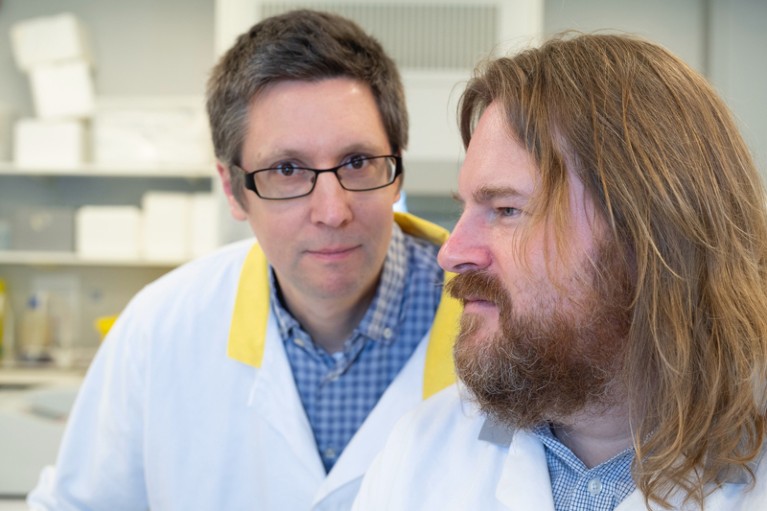

Wass heads a joint research group and credits his co-leader, molecular biologist Martin Michaelis, for keeping him tethered to the world of research. “Martin is always there to talk to me, make sure I’m engaging with things and keeping up with group meetings every week,” says Wass, which ensures that he stays in touch with laboratory members.

When he took over as head of school, Wass negotiated that one day a week would be set aside for his research and teaching. Like Wingfield and Geher, he blocks out large chunks of time in his diary to focus on research, rather than trying to fit slivers of it in between other meetings. “I struggle with this idea of having little bits of time and being able to switch” back and forth, he says. “I need at least half a day so that I can start something, really get into it and make some progress.”

Computational biologist Mark Wass (right), who is also head of the School of Biosciences at the University of Kent in Canterbury, UK, credits his group’s co-leader, molecular biologist Martin Michaelis (left), for keeping him involved in the group’s work.Credit: University of Kent

Another strategy to stay active in research is to attend conferences. “I make sure I go to some conferences so that I’m still hearing about the research that people are doing, and continuing to keep up that network of people I know and engage with,” says Wass, who says he’s likely to sign up for another three-year term as head of school. Administrators say these positions do have upsides for their careers, in the form of new skills, an enhanced profile or being able to implement changes in their department (see ‘Why did I sign up to be department head, again?’).

Back to full-time research

The researchers all say that universities need to recognize the value that scholars bring to these roles, and reward and support them accordingly. Many institutions offer a sabbatical — a set period to focus solely on research without any teaching or managerial duties — to researchers who have completed their time in administration. But often, faculty members must negotiate for a sabbatical — typically by raising the issue to start with.

Higher-education scholar Teboho Moja completed her term as chair of the administration, leadership, and technology department at New York University in August and is now on sabbatical. Even though she continued to publish research and attend conferences while chair, she will use the sabbatical to “reset myself and work out my research agenda”, she says. “I will focus on work that I put on the back burner while I was doing administrative work.” These projects include working on her autobiography, guest editing a journal and completing two fictional books for children.

But sometimes the bureaucratic demands become overwhelming, and scholars struggle to keep up with their research. The situation is very common and understandable, says Geher. “If someone finds themselves in that position and wants to get back into research, they must carve out ‘holy time’ that includes obligations to other people, such as students.”

While she was deputy dean of research at the University of Pretoria, plant geneticist Brenda Wingfield took over a boardroom one day a week to confer with members of her research group.Credit: Eye Scape

Having a network of early-career team members also allows researchers to make the most of a post-administration sabbatical, he says — in his case, it meant that he was “ready to hit the ground running”. He met with his students once a week and “by the end of my first semester back, we had some very cool research projects in motion”.

It is also crucial to structure a sabbatical by setting deadlines and writing them down, he says. “Remember that procrastination is the enemy of any good sabbatical.”

A sabbatical also offers an opportunity to become involved in new branches of research. Wingfield used her post-administration sabbatical to investigate ‘mating-type’ genes in certain kinds of fungus, and this led to highly cited papers and remains a focus of her group today, she says. During another sabbatical, she broadened her research to genomics-based studies. “This marked a new research direction, which has resulted in my being awarded a research chair” through the South African Research Chairs Initiative, a national award with dedicated funding, she says.

Even if someone has been on a hiatus lasting years from their research, “you’ve clearly got a grounding, and you’ve got some networks”, says Wingfield. “You just have to go back to basics.”